Several days until I record the Berio Sequenza no. 1. This winter break has been very stressful. I was with my family in St. Petersburg. Family can be stressful, my son is at a difficult age, I myself am at a difficult age. Russia is stressful. It was so cold that it has taken my skin and lips days to recover. But now back in the saddle of my bicycle in the temperate zone of Northwestern Europe, I have hit my stride.

I am allowing myself a luxury. Next week there are plenty of pieces to prepare, old and new, but I decided to forget about them and devote my practice time to concentrate on Berio.

The main reason is that my body feels soooo much better when I keep my practice time to only a few hours a day. This is how I want to feel during the recording. So I warm up, play Bach for sound, articulation, style and focus. (Watch Pahud’s video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yUxY7tagf0g where he gives his ideas on playing with focus. I practice like this with either one or two movements of Bach. I don’t recommend learning new pieces like this, but with pieces you know well, it is a great lesson.) Then Berio. Then for the rest of the day I do my Helen stuff, read, hang out with family, watch dumb and smart stuff on Youtube, study Jazz. This is luxury, as I have said. No rehearsals or teaching this early in the year.

This time around I thought I would re-visit Gazzeloni’s recording. Just because. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4SVeJhagG1I)

It reminds me of a conversation I had with Camilla Hoitenga about new scores and recordings. You receive a new score along with a recording by the person for whom the piece was written. So you dutifully sit with the score and listen, but so much doesn’t correspond. So how do you prepare, follow the score or the recorded performance? You assume the player worked closely with the composer, and the composer is happy with the recording otherwise s/he wouldn’t have sent it to you. Even though I am sure I have been that player/dedicatee, I still don’t have an algorithm to navigate this situation.

Since Gazzeloni’s recording is very much of its own time, I doesn’t spin me into a crisis. I find it very revealing though. I won’t end up following his tempi, but there are quite a few turns of phrasing that inspire me to think differently.

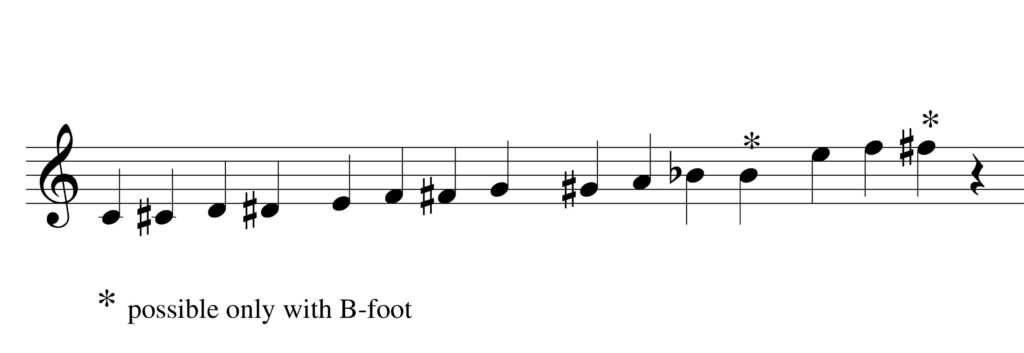

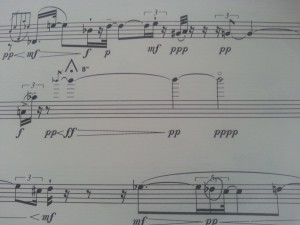

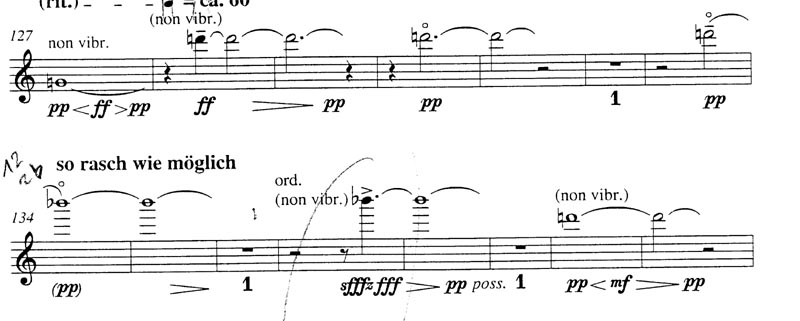

About the tempo. I was talking to another local flutist who had worked with Berio on the Sequenza. He told me Berio complained that most players “play it too f(*&^ing fast!”. Well, I have news for you, Sr. Berio. You wrote it too f(*&^ing fast. Funny that the new edition doesn’t even adjust the metronome marking.

I have also enjoyed watching Paula Robison speak on the subject. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=irY1kHq_F3g) In the last section, she points out possibilities that Berio allows (one namely being a slower tempo). I was also interested to hear about how she connects the Sequenza to the works of Samuel Beckett. Through Berio’s electronic piece, Thema (Omaggio a Joyce), I was aware of the James Joyce connection, and Beckett does make sense. Through playing Rebecca Saunders music, I am quite familiar with some of Becketts’ texts. So another inspiration has surfaced 🙂

One big influence on Berio that I think really should be mentioned is that of the musicians around him, namely, his wife at the time, Cathy Berberian, for whom he wrote the third Sequenza. Her theatricality, her agility, never cease to inspire me. Only recently did I come to know she composed herself. Here is an example of her graphic score, Stripsody (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XHUQFGhXHCw).

I love her recording of the vocal Sequenza too, but I just came across a recent recording of the Sequenza no. 3 for voice by a young singer, Laura Catrani that fascinates me. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E0TTd2roL6s). I can’t aspire to this type of recording, but it does give me food for thought.

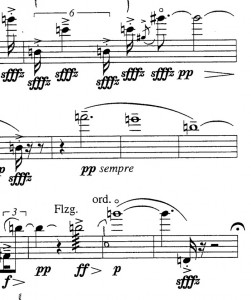

I am unashamedly playing from the old edition. Being a creature born myself in mid-20th century, I am hoping the good people of Universal Edition will forgive me. The old version has been in my memory for about 20 years now. But I do own the new addition, and am finding it more useful than ever this time around to answer questions about timing. For an interesting discussion of the two versions you can read Berio’s Sequenzas: Essays on Performance, Composition and Analysis, Chapter one by Cynthia Folio and Alexander Brinkman.

I am unashamedly playing from the old edition. Being a creature born myself in mid-20th century, I am hoping the good people of Universal Edition will forgive me. The old version has been in my memory for about 20 years now. But I do own the new addition, and am finding it more useful than ever this time around to answer questions about timing. For an interesting discussion of the two versions you can read Berio’s Sequenzas: Essays on Performance, Composition and Analysis, Chapter one by Cynthia Folio and Alexander Brinkman.