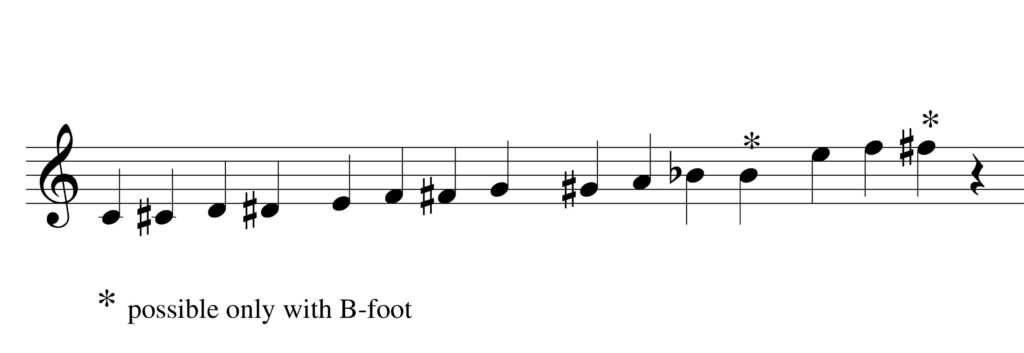

Harmonics (also called overtones or flageolets) are great! I love playing them, but I want to mention several issues when writing them for flute, piccolo, alto flute or bass flute. The most prevalent mistake is writing harmonics that are too low. The following notes cannot be written as harmonics:

The above notes can only be used as a fundamental for a harmonic/overtone, but cannot be a harmonic itself. This is logical, because in produce a harmonic, you need to overblow a note beneath it. Since this is the flute’s first octave, there aren’t notes beneath it available to overblow.

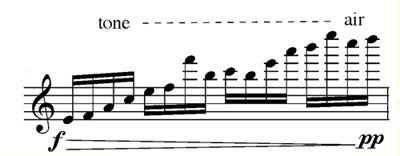

Another issue, I will call it a misuse rather than a mistake, is writing quiet harmonics in the upper half of the 3rd octave up to the 4th octave. I suspect when composers write high quiet harmonics in these octaves, they are imagining a sort of color that a violin harmonic can produce in that register: thin, ethereal, a bit breathy, maybe just slightly (and only slightly) out-of-tune. Or perhaps they might believe that a high quiet harmonic is easier to produce than a high, quiet, regular note. Well, folks, it doesn’t work like that. To get the upper partials on a flute, you have to blow like hell if you want to produce notes with more than 4 ledger lines above the staff. (Someday I will make a funny video on the subject for your amusement.)

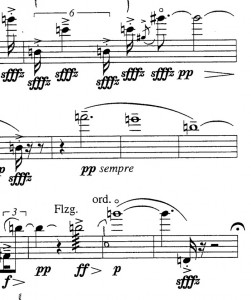

Now if you have done this as a composer, you are in good company. Berio did it in the Sequenza. Generations of flutists have tossed around different solutions, alternate fingerings, whistle tones, anything to avoid playing an actual harmonic!

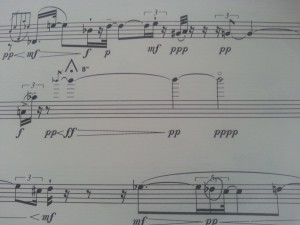

Wolfgang Rihm has done this too. Here are two examples from Nach-Schrift. Once again, the Bb. The D proceeding it works well as a G harmonic.

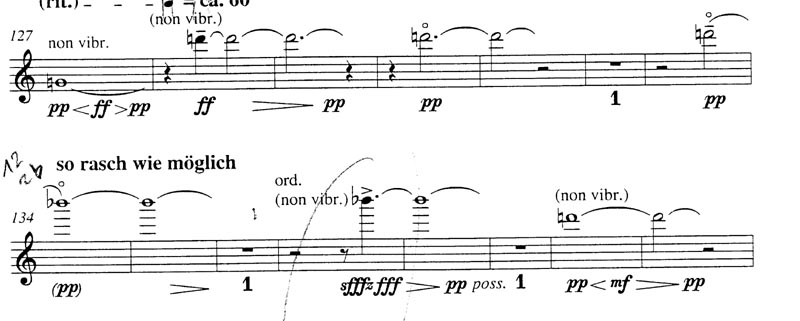

The following G# harmonic is borderline because it starts loudly, then one can change to the normal fingering. The G after that is also borderline. You can see that my predecessor overblew it as a C, but for me that would be too flat.

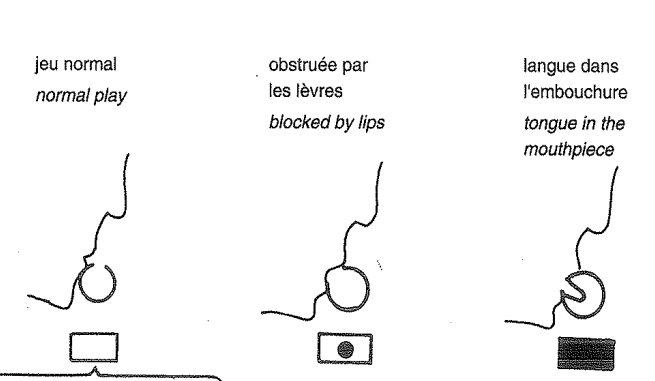

If you have read this far in order to get a hard-and-fast rule, I must disappoint you. I think the 4-ledger-line rule (as seen in the high G above) is a good guideline for my abilities, but there might be other opinions out there. Just please be aware that very high, quiet harmonics on the flute can not match the delicacy of a violin. An experienced player can indeed match such a sound, but will do so not by overblowing a resistant lower partial, but by using an alternate fingering that adds ventilation and reduces resistance.