Actually, this is a “notes-to-self” entry disguised as “Tips”. There are good sources for learning and practicing multiphonics such as Robert Dick’s “Tone Development through Extended Techniques” (although I know the term “extended techniques” has gone out of fashion, but the practice in the book is solid). I also have a detailed presentation where I approach learning multiphonics through the study of flute harmonics and spectral hearing. If you know of any other learning materials, please share them in the comments.

Now to the notes-to-self. It is well and good enough just to learn and practice multiphonics, but time has shown that one is often asked to perform multiphonics under less-than-ideal conditions. This goes especially for ensemble pieces when there are others playing, and it is difficult to get aural feedback from your own playing in order to make the minute adjustments necessary to play a multiphonic. However, in solo works there are also challenges, where a multiphonic might be difficult to approach in context (in a series of them, or after a particularly tiring passage, for example). So how do I prepare for that? Part of the answer is simply training in-context, as well as the reassurance that experience will bring. At times it is helpful to ask yourself, or the composer, conductor, or chamber-music colleagues which note in the multiphonic is of most importance? What voice should I bring out? Perhaps most important of all: can I find a better fingering?

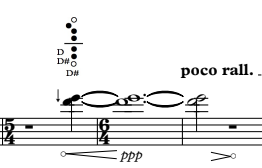

And sometimes the composer thinks that he/she is helping by saying “oh that’s ok, I want an unstable sound, you can vacillate between the notes”. OK. That is something that has to be practiced too, because often a vacillation comes with a sudden jump in dynamic. In most cases, this is not the effect the composer is going for. This led me to a practice that I think is very helpful for close multiphonics such as this one (taken here in context from Joseph Lake’s Concerto for Prepared Piano):

I should emphasize that the basic way to approach a multiphonic is to take it apart, get to know the dynamic range of all the notes, do the throat tuning to the weakest, etc. etc. These steps have been covered in tutorials by myself and others. But once this has been done, we often get caught up in trying to get both notes equally, and then still failing. In past tutorials, I talk about using fluttertongue to help find the position of the tongue that will work, and listening and aiming for the difference tone or beatings of the notes rather than the two notes themselves (logically, aiming for one thing is easier than aiming for two, right?). Another trick to throw out is to practice this vacillation that composers are so fond of – slowly. If you can control going between the notes slowly, and minimize the jump in dynamics that sometimes accompany the movement, I find that the actual multiphonic sounds more than you expect.

So those are my thoughts from today’s practice, if you have anything to add I would be curious to know.