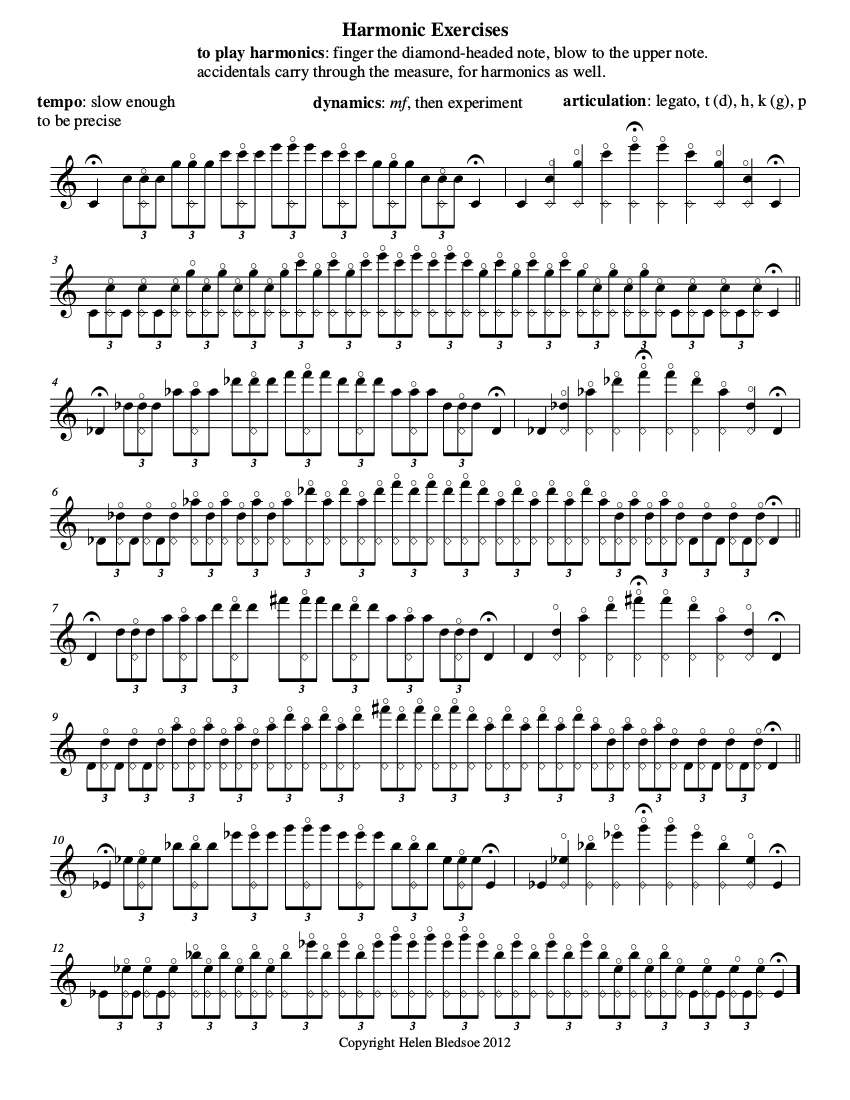

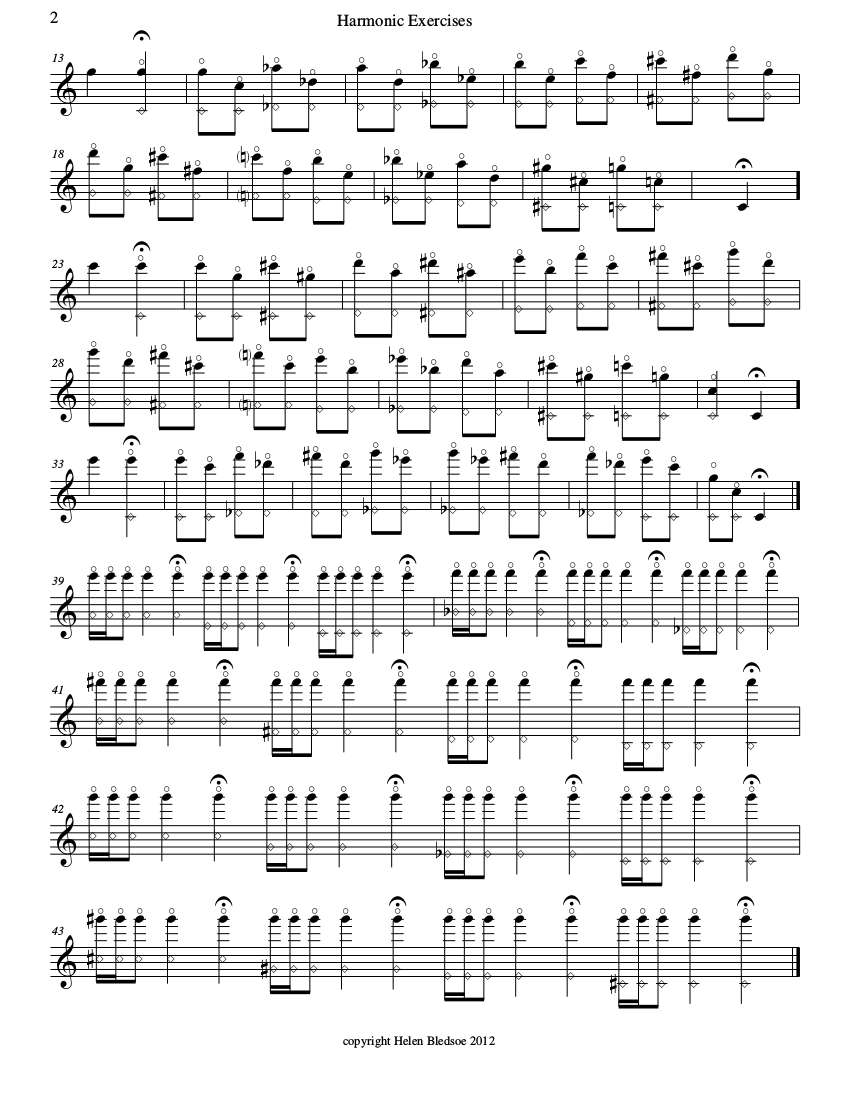

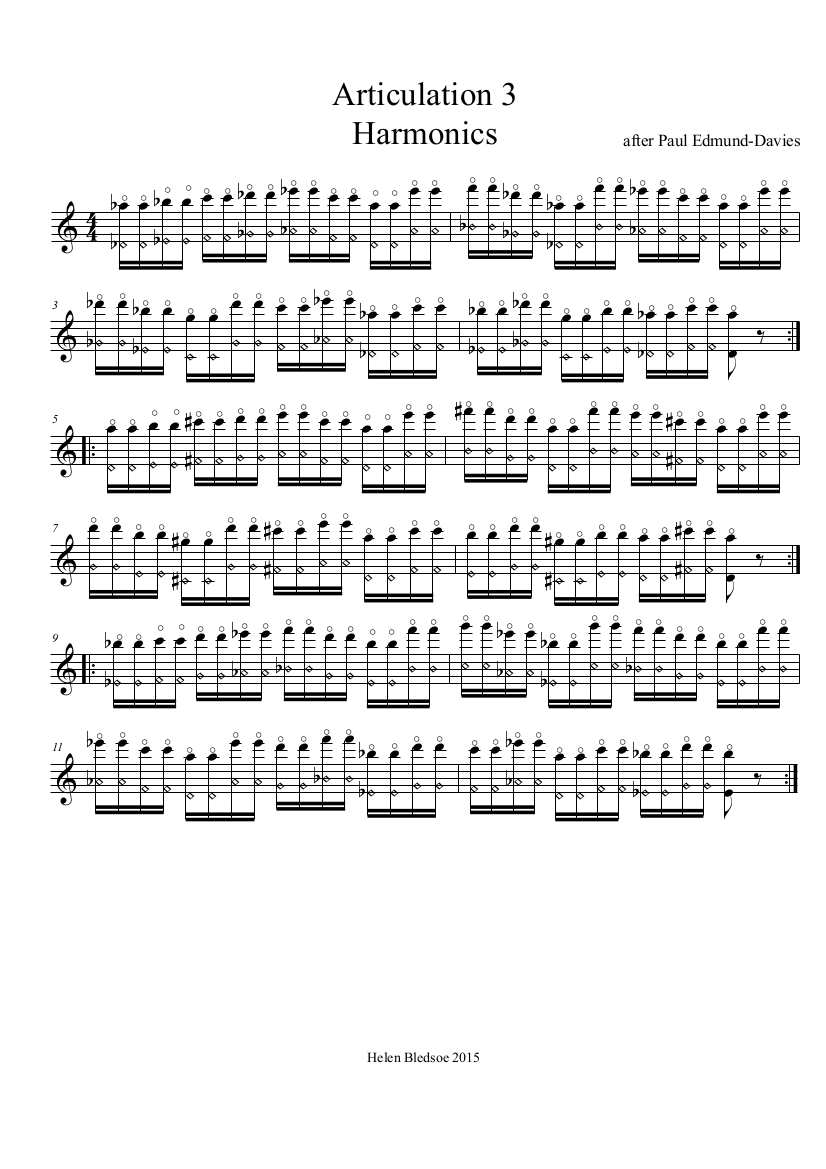

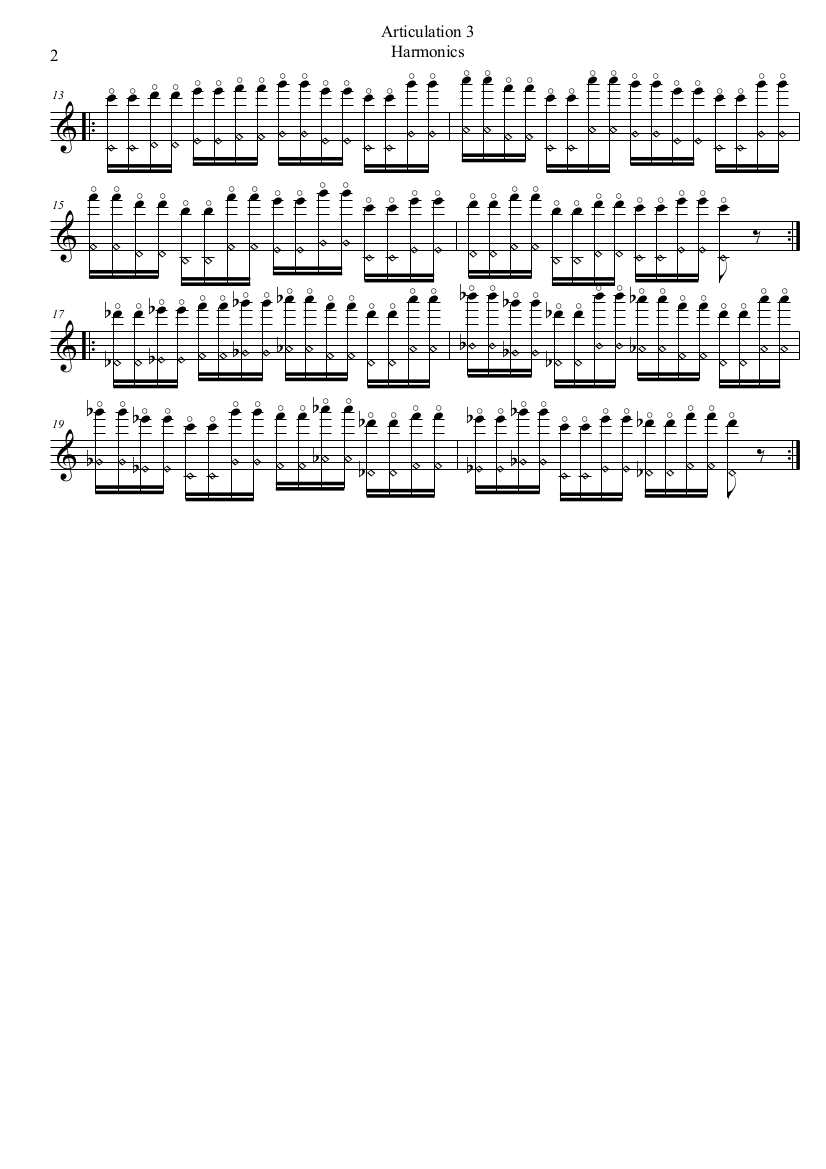

To get started before doing the exercises specifically for piccolo, have a look at this exercise on page 5 from this collection of harmonics exercises (sorry the pages are not numbered). For some reason, I find them especially beneficial for piccolo. It’s good for developing awareness of exactly what combination of physical actions you need for going high – abdominal support, embouchure, placement of the tongue and jaw, and notice how the throat sometimes tries to help. Very kind of it, but not necessary 🙂

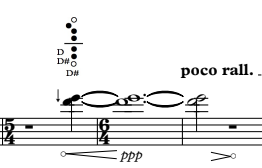

This preliminary harmonics exercise will help with the challenges found in these two piccolo warmups which I have developed over the years. The first is meant to be quite slow, ideally to be played with a drone / tuner on the fundamental. The second is of course a rip-off of TG EG no. 1 and Mozart, but it works esp. for articulation and agility with large intervals. It’s kind of a killer when you go high, so take it easy if you are new to the piccolo.

Composers often write for the piccolo not only because of its high frequencies, but because of its agility. That requires strength and training, and smart body awareness in order to avoid injuries or strains. Also, please protect your ears while practicing! If you don’t have professional earplugs, I find the silicone ones (also used for swimmers) quite good, you don’t even have to stick them inside your outer ear canal, just a little bit to cover the opening of the right ear is sometimes enough for me.