[This is an excerpt from a questionaire sent to me by Lorenzo Diaz for research purposes. The answers represent my opinions only.]

Do you think conservatoires and schools of music really attach importance to contemporary music education?

My short answer to your question is “not really” because I think a “Comtemporary Music Education” should require not only teaching contemporary repertoire and its extended techniques, but should also require learning extended use of rhythms, different tuning systems, composition (especially for the performers) and improvisation.

Here is a longer answer: An increasing number of schools do attach importance, at least formally. In Europe, the Bologna process has helped by offering specialized Masters programs such as Masters in Contemporary music. The appearance of prestigious Academies and Festivals such as the Lucerne Festival, the academies of Ensemble Intercontemporain and Ensemble Moderne has helped to draw conservatory students’ (and their Professors’) interest.

I am not sure if this is happening outside of Northwestern Europe, but here there is a trend, usually initiated by Composition Departments (not Instrumentalists!), to create formal student Contemporary Music Ensembles, and hire personnel (part-time) to run it. This is a great thing, it creates jobs, gives the student composers an outlet for performances, and gives instrumentalists a chance to play contemporary music and receive formal credit.

These are formal, structural changes that I have witnessed in the past 20 years.

Although I have listed positive changes above, I think still in many schools there is a lack of integration of repertoire from the late 20th/early 21st Centuries. Personally, I would like to see Composition Departments taking even more responsibility and action to help make the needed changes. It can’t come from instrumentalists alone. Composition teachers could do this by focusing more on teaching the basics of Instrumentation/Orchestration, which is becoming a lost art. This would avoid basic mistakes and misunderstandings that can lead to distrust. They could encourage more programs or situations that encourage collaboration between student composers and instrumentalists. (Such as creating, taking part in or seeking funds for programs like Composer Collider Europe.) When a piece of contemporary music does not go over well with a student, they and their teacher are likely to criticize the music or the composer, rather than to criticize the situation that provides little opportunity for collaboration, preparation and practice.

In your opinion, is teaching extended techniques really necessary in the academic environment?

I think it is necessary to be able to offer them. They are part of some required repertoire for competitions, and can assist in embouchure development and control of the air stream. However, there are great flutists today who have never utilized extended techniques. I would not say it is absolutely necessary, but it is practical.

To be completely honest, I think that to be a contemporary musician, on the technical level it is of first importance to learn the complexities of modern rhythm (polyrhythms, odd time signatures, etc.) and intonation (microtonal, spectral tuning, etc.). This will strengthen a student’s sense of rhythm and intonation, skills that are necessary to find a job in an orchestra, ensemble or theater. Learning to improvise and compose (just so you have experienced the process that a composer goes through) are the next most important things, to make one more completely rounded. Where do extended techniques come in? Again, I think it depends on the student, if and when they need it for embouchure development, or to play certain repertoire, or to expand their improvisational vocabulary.

Do you think conservatoires should include more musical works using these resources in their academic programs?

I think that more exposure to works with extended techniques should be encouraged. Repertoire with these techniques is becoming standard for auditions and admissions to festivals, competitions and places of study.

In the case you reckon that the study of these techniques in students of elementary and professional level is possible, which technique (or techniques) would be preferable to apply from the beginning? Is there any one in particular that would be rather applied later on?

It really depends on the student. If there is already the range of an octave, and the student has a good understanding of how to coordinate the air and embouchure, then harmonics can be introduced (we need the technique of overblowing anyway to play notes in the second octave). Circular breathing can be introduced as a concept from the beginning through the use of a glass of water and a straw, or the use of an end-blown tube like the didgeridoo. Application to the flute would come later, once the student has developed a good concept of embouchure and is flexible enough to come back to it after the modifications necessary for circular breathing.

Is there any technique in particular that has proven to be more effective throughout your study?

Harmonics are the most basic, I always turn to them in times of trouble.

Do you usually request your students to study some effect on a daily routine, just as well as any other given technical exercise? If so, which one?

Again it depends on the student. Harmonics are good for anyone, and I encourage all students to practice them daily.

The “trumpet sound” has aroused controversy regarding its use; flautists as R. Dick would rather it not be written in order to avoid a counterproductive effect in the lips, do you agree with this?

The counterproductive effect is only temporary. I use this effect in improvisation, however I discourage composers from using it. I have little faith that it will be written in a context where it will be appreciated acoustically or in a way that will avoid the counterproductive effect.

Do you usually use any of the following extended techniques, both on your study and with your students (daily, at any given time…)

Air: Yes sometimes. In a conversation with Sophie Cherrier, I got the idea to spend 10 minutes a day on loud air sounds in order to get the air column working. Of course, she does not recommend doing this with students who already have too much air in the sound, but for those who are too tight or too focused, this really works. I do it myself when I remember.

Voice: Yes, I recommend this to my students and have exercises for it.

Whistle tones: I teach these as needed. There was a time that I played these every day in order to play the first octave whistle tones down to low C. That was hard, but once I could do it I don’t need to do it every day.

Bamboo: Only on request or as needed in the repertoire.

Flutter tongue: Sometimes I recommend this as part of articulation training. Aurele Nicolet recommended that fast, articulated passages should be practiced legato and with fluttertongue.

Pizzicato: Only on request or as needed in the repertoire.

Key clicks: No. I try to discourage composers from using it. Pizzicato is much more effective.

Jet whistle: as needed, some players think it opens up the sound of the flute.

Circular Breathing: I teach sometimes, on request. Benefits can be as a checkpoint for resonance. When I am warming up or just about to go onstage, I check my circular breathing regardless if it is required in the piece I am about to play. This is a sure-fire test to see if either of my nostrils or the back of my throat is blocked. If I am clear enough to circular breathe then I should be able to play with maximum resonance.

Tongue Ram: In conversation with Sophie Cherrier she mentions that she sometimes teaches Tongue Ram in order to get a student to activate the abdominal muscles. This is something I plan on doing, should I have a student who needs this. I have tried it myself, not something I do every day, but occasionally it is a good activator.

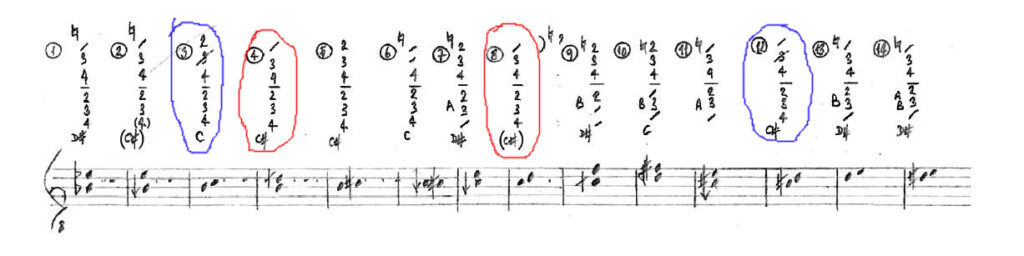

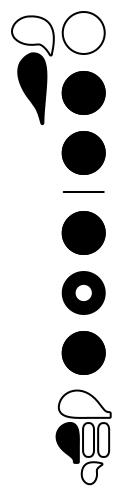

For more information about the benefits of extended techniques, please see this handout.