I am astonished by the occasional vitriol I encounter from some prominent flutists when it comes to extended techniques such as multiphonics, circular breathing and so on. They chant the same nonsense: “bad for your embouchure”, “waste of time”, “don’t be one of those players”. After over 20 years of experience with these techniques as a player and teacher, I am convinced of their benefit to traditional playing. But that’s not what I want to post about. I would like to approach this question from another angle.

Some years ago in an active network forum a very prominent flutist remarked that flutists who can circular breathe belong to a certain class of players whose time would have been better spent working on learning to play properly. I won’t delve into the implications here. It made me livid. I spent 11 weeks in 1992 learning to circular breathe, did that hinder me from playing properly? How idiotic! This person has somewhat recanted this initial statement, but the shadow of stigma still applies in some circles.

Now I have 5 years experience teaching at the conservatory level, and I’ve begun to understand this attitude. I won’t say I sympathize, but I understand it enough to offer some insights which I hope will help students, teachers and composers. There are two issues, as I see it.

The first is a basic misunderstanding. Here is an illustration – this semester I had a student who was swamped with student ensemble compositions and several 20th century repertoire pieces. After this period, she came to me with an 18th century work. The sound was bad, no focus, articulation stuck, breathing shallow. She had tied herself into knots because of the difficulty of the contemporary works, which included circular breathing, microtonality and switching to alto and bass flutes. A typical teacher’s reaction would be “OK, see what that stuff does to you? No more!” But folks, the music itself is not at fault, it was the student’s attitude toward it that stressed her and put her practice into panic mode, causing physical problems that set her way back.

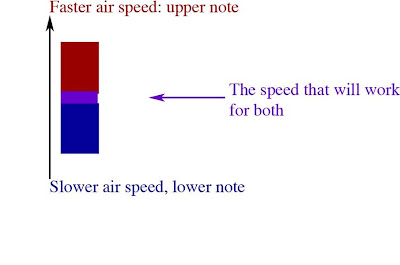

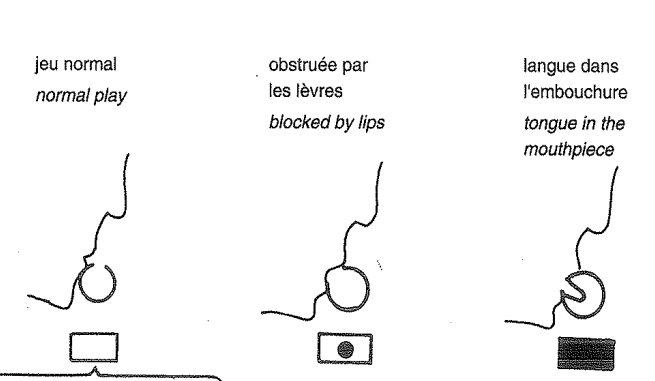

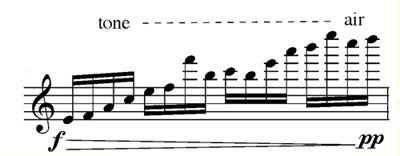

That can happen with any repertoire. It can happen when you first learn to play the piccolo. Good and balanced practice on the piccolo can help and enrich your flute playing, as can good and balanced practice of extended techniques. Managing the airstream and angle for piccolo playing is also an extention of flute technique. Exercising the same management for multiphonics is not such an “out-there” thing.

It wasn’t for nothing that Aurèle Nicolet always said: “You must play Baroque music every day, you must play Bach every day!” If you practice extended techniques as a true extension of good practice out of good flute technique, you won’t fall back, or at least if you do, the recovery time will be very quick.

However, there is another aggravating element, which leads me to the second point, the disparity between composing and performing. Student composers don’t necessarily need endless years of training to write very complicated music. Student instrumentalists and singers need decades of training before they acheive the level it takes to play a complicated piece it took a student composer only one semester to write. I’ve put this rather crudely but you get what I mean. Since being a composer-performer is not really encouraged by the conservatory system, this artistic link has been severed. Our only hope is diplomacy! Communication of the issues of difficulty is very important. Encouraging an us-versus-them attitude will make the situation for both worse.

When a flute student is first exposed to contemporary techniques at the conservatory level, it is likely s/he will be overwhelmed because that first exposure may be a standard repertoire piece written for a professional [think of all the works written for Pierre-Yves Artaud, Robert Aitken, Roberto Fabricciani and so on], or written by a student or faculty composer who assumes that level as the norm. The student is frustrated, the teacher, if inexperienced, is also frustrated and there’s another black mark against contemporary music. The earlier good, measured, positive exposure to extended techniques, the better.