In previous posts on Ferneyhough’s music, I describe my approach to his complex rhythms. It is worth noting again that his music is not pulse based; rather, the measure is considered a “domain of a certain energy quotient”.

In Cassandra’s Dream Song we are presented with freedom from measures, time signatures, or metronome markings. The Italian indications often refer to character more than actual speed: lento analitico, grazioso e rubato, molto rigoroso. So how fast do we play it? I can give no answers, but hopefully my ideas can give a clue as to what may work for you.

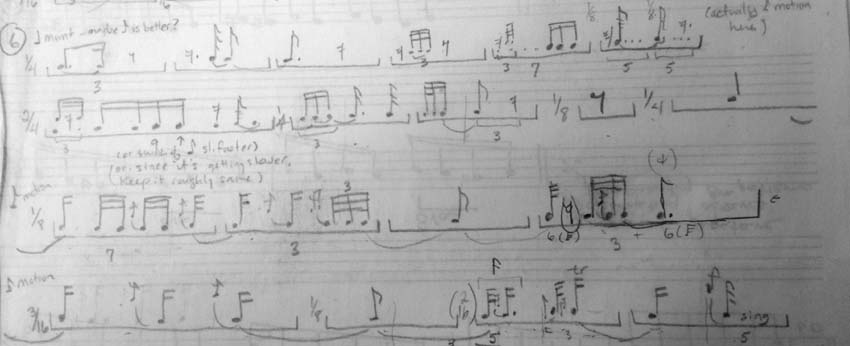

If you carefully sketch the rhythm of a passage, the spatial relationships become apparent. Here is a very old sketch I did of line 6. I attempted to make measures out of the gestures – an idea I later abandoned in favor of pure spatiality:

Personally, I find this line is often performed too fast. I am guilty of this as well. Who doesn’t get excited by those closely-written, many-beamed tuplets at the end? But if you look carefully, I believe there is a compositional reason for those multi-beams. The beginning of the line has a sort of quarter-note feel to it. Under the first heavy arrow (indicating ritardando), the eigth-note becomes the rhythmical basis of movement (see, I try to avoid the word “pulse”, but maybe I am being too pedantic). By the A-natural things have slowed way down: lento molto con forza! (Composer’s exclamation point). That is one very long note, relatively speaking. By this time, like a compositional microscope, the rhythmical basis has magnified to the level of the 16th note. And then there is another ritardando! (The heavy arrow). It is as if we are being drawn even further through the lens of this microscope, experiencing progressively smaller units of the beat as time proceeds. Finally, we come down to the “atomic” level of the piece. It is an amazing ending.

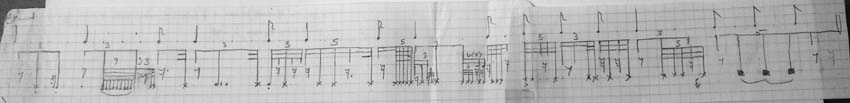

After analyzing several lines like this, I abandoned the idea of imposing measures and transferred the sketches to graph paper in order to see the accuracy of spacing as clearly as possible. Here is an example of line 4:

I did all this work not only to have a chance of playing the rhythms accurately, but as a crucial step in deciding: how fast? You have to find which notes are really the fastest (sometimes not the ones that look the fastest), and go from there. How fast you play will be an individual decision. I am not convinced there is a global metronome marking that works for the entire piece, but maybe someone else has another opinion. I do think the flow should be consistent within an individual line – with close attention if there are indications of change.

In this entry, I present these sketches so that if you are interested in the piece, you can have a go at it yourself. The rest of the sketches are too large and lightly written to scan well. Please don’t ask me to scan or photograph the rest and post them (and not every line has been analyzed). However, I am happy to show them in person.