This summer, for better or worse, I find myself without paid work for a whole month, so I have flown off to St. Petersburg with my family to enjoy the last of the White Nights. With one week left, I spend my vacation practice mentally preparing that which I have to play from memory, and mulling over thoughts about what is actually involved in creating musical expression. Once again, I have no particular point in this entry, just an accumulation of thoughts.

One of my goals this summer is to read Constantin Stanislawski’s “An Actor Prepares” in the original Russian. It’s very slow going, which is good in a way, since sometimes I tend to read too fast and not retain things. Theatrical, artistic expression is a big topic (so far) in the book, but I am wondering whether it is worthwhile to draw parallels to musical expression.

Playing a solo part has obvious parallels to playing a role in a theatrical work, but is it useful for musicians to really experience the emotions we are trying to convey, as an actor is encouraged to do? Stanislawski himself points out that experiencing the emotions is not enough. There has to be technical control over the use of one’s body and voice above and beyond feeling. I think that is the crux for musicians.

Playing a solo part has obvious parallels to playing a role in a theatrical work, but is it useful for musicians to really experience the emotions we are trying to convey, as an actor is encouraged to do? Stanislawski himself points out that experiencing the emotions is not enough. There has to be technical control over the use of one’s body and voice above and beyond feeling. I think that is the crux for musicians.

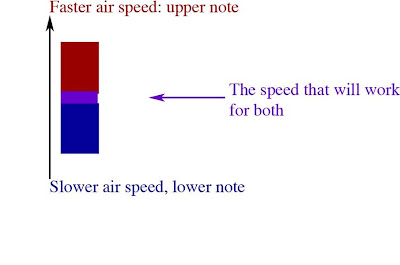

Here’s something that probably happens to most of us: I can really “go for it” in a high, ecstatic, fortissimo passage, passionate, all systems going full steam. However, if I really do that, my heart will be racing, and my center of energy and balance will be too high. If there is a sudden dynamic shift, I am up a creek, breathless, heart thumping, out of focus. Even in the moment of passion, there has to be a part of yourself that stays sober and reminds you to stay down, open and be ready for what’s coming. That part, I guess, is our technique. It is the balance of that sober part to our ecstatic part that makes our practice and performance so exciting.

I remember one thing Robert Dick told me. In abstract contemporary music, we often can’t rely on the use of recognizable rhetoric, or the Affects we learn about in Early Music. Sometimes we can’t even rely on the expression of anything recognizably human e.g., sad, happy, sensuous, hideous. However, what the audience will recognize is energy. That is what we must aspire to conjure. It may be that your energy will not be interpreted as you intended. I can’t tell you how many times this has happened to me, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse.

I’ll leave off by sharing a video with Barbara Hannigan, who talks about her preparation for the role of Alban Berg’s Lulu. Few of us have the luxury of this deep level of preparation, but I found her dedication very uplifting. (ed. – In case you don’t make it to the comments section, here is another recommended video with Stephen Fry discussing the visceral experience of opera: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EVN4dShaZWk.)