Some time ago I decided to devote at least a few minutes of my flute practice time to singing. Long story as to why, I won’t go in to that here. But the decision to sing, and the upcoming workshop I am giving at the Adams Flute Festival on Sunday April 15, 2012 inspired me to put together these ideas.

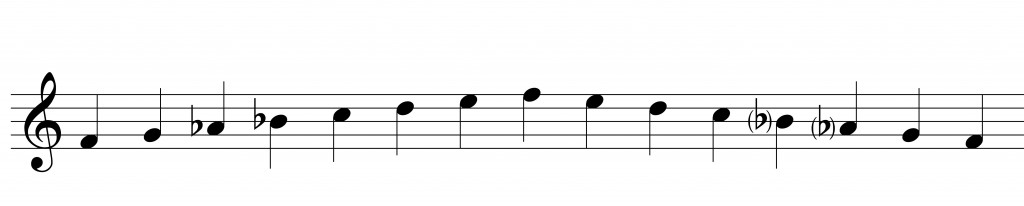

Throat tuning is the best basic application of singing and playing. Tuning your throat to a pitch you want to play will help you to achieve maximum resonance. You can find a more detailed explanation in Robert Dick’s you tube videos and his exercises from Tone Development Through Extended Techniques. Here one of the exercises he demonstrates. This exercise is also much loved by Peter Lloyd:

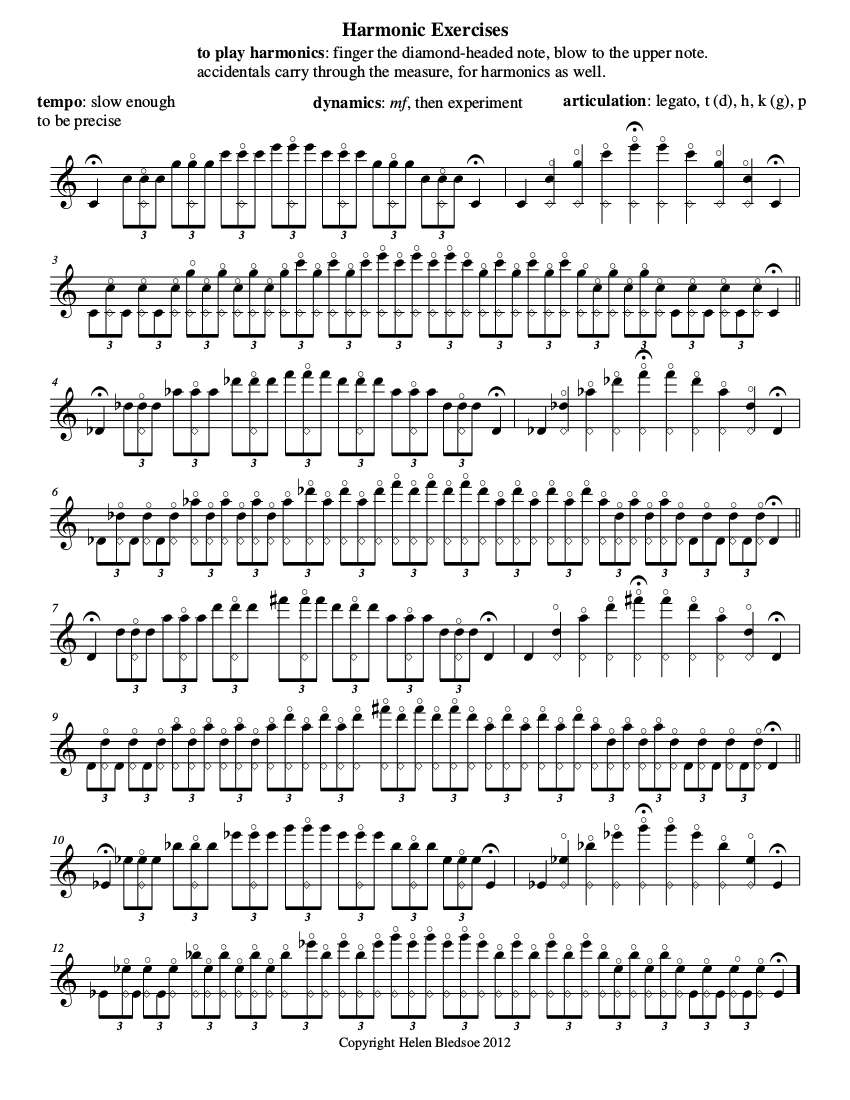

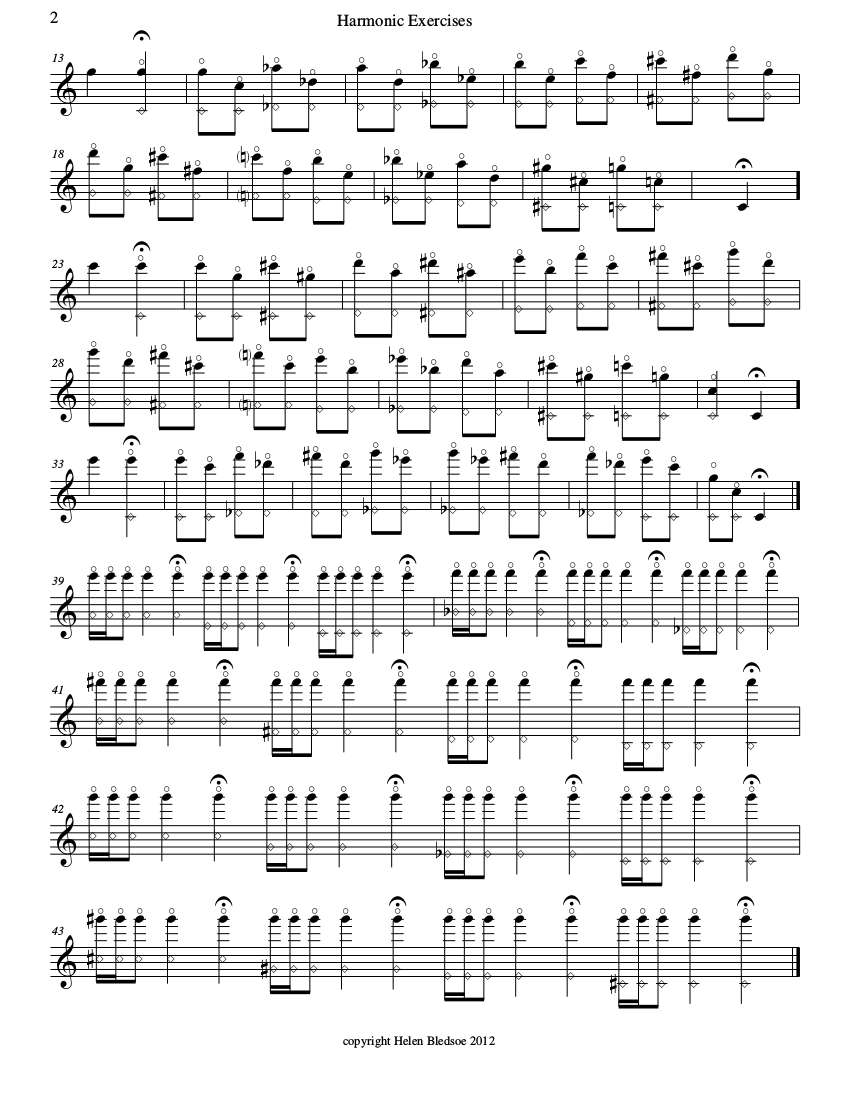

You can start with Taffanel & Gaubert’s first daily exercise in any key. I have chosen B-flat because it falls easily in my range. You can also choose any octave you wish. In case the musical example is not clear, here is what you do: 1. play the first 5-note pattern, 2. sing the 5-note pattern while silently fingering the notes on the flute, 3. sing and play together, 4. play only, but keep the feeling and resonance as if you were singing and playing. You may notice a big change in your resonance.

Another application of singing and playing that I like to utilize is to use singing as a check-point for keeping a relaxed throat while playing high notes. If you can sing a low note while playing a high one, then likely you are using your embouchure and support correctly. If you can’t produce a low note while playing high, you are likely squeezing your throat in order to “help” the high notes out. That’s the easy way out! A good high register, though, has its support down below, and the lips do the work of narrowing the passage of air, not the throat.

To experiment, play a high note (any will do, I have G here, but you can go higher or lower) and see how high and especially how low you can sing while holding that note.

To experiment, play a high note (any will do, I have G here, but you can go higher or lower) and see how high and especially how low you can sing while holding that note.

You will hear many strange difference tones while doing this; as your voice goes up, you may hear a “ghost” glissando going down, and vise versa. Being able to create this effect is application I love about singing and playing. Some composers use it effectively, and it also comes in handy when improvising.

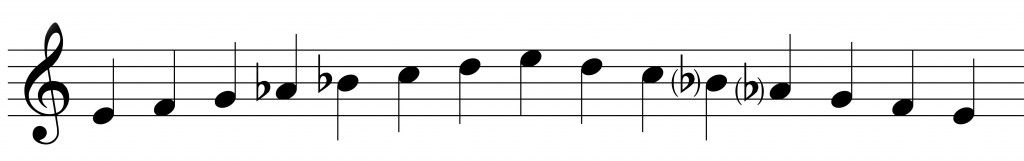

Now, back to the point about keeping the voice low: try playing octaves and keeping the voice in the lower octave. Keep the voice steady on pitch. Again, you can choose any key and any octave:

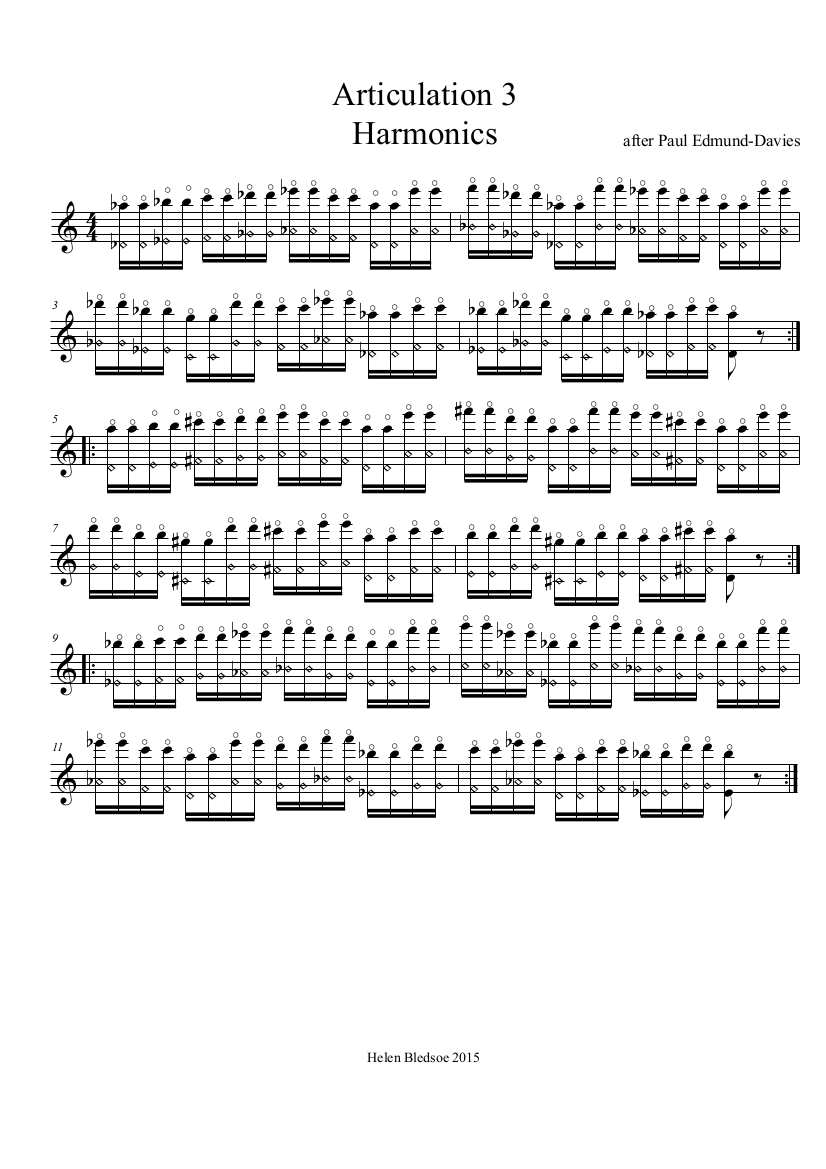

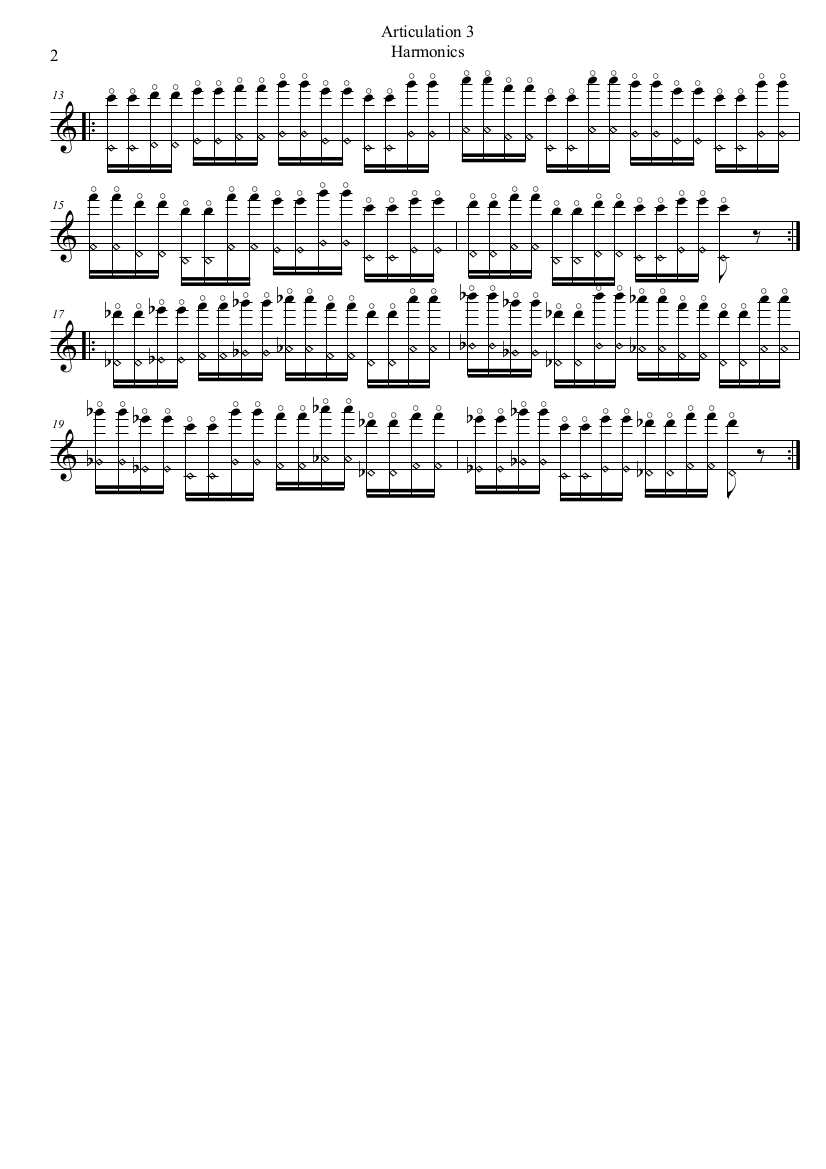

A bit trickier is to keep the voice on a single low pitch while blowing through the harmonic series. If you aren’t familiar with the harmonic series, better to begin without singing. Don’t worry about getting the highest notes at first. Work your way slowly up.

C is a good note to start on, but you can choose another. Also, don’t be discouraged if you can’t produce the highest harmonics while singing at first, just work on getting them one at a time, no vocal glissandi allowed here!

And just because I am a bit fanatical, I wrote a vocalise to one of Reichart’s daily exercises. The voice sings the top line:

If anyone wants the whole exercise, you can click the link here. You may distribute it, but please give credit where it is due.