I’d like to take the opportunity to write about the benefits of doing intonation exercises with 3rds and 6ths using just intonation.

- To refine the ear. These are simple intervals, and the difference tone (or combination tone) is strong enough to easily adjust.

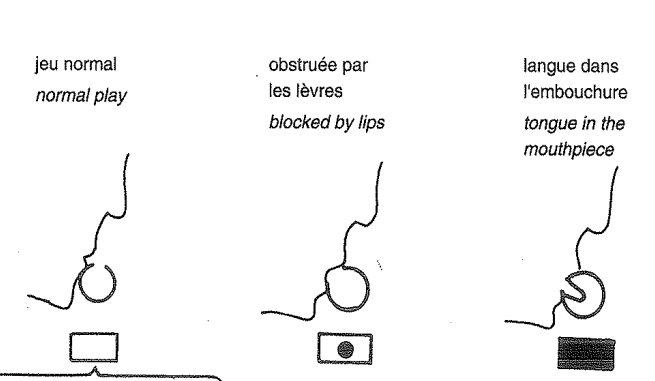

- Flexibility. To make these adjustments, a flutist must be willing to make minute changes of the angle of the air by manipulating any three points: lips, jaw, or rotating the flute in or out.

- Accuracy in tuning chords (vertical intonation). The theoretical knowledge that, from the bass note, major thirds are 14 cents flatter and minor thirds 16 cents sharper will cut out some of the fishing around for the right direction. (That’s thinking like a flutist. Objectively stated: major thirds are narrower, minor thirds are wider.)

- Grasp of microtonality. Seriously. Take the second bar of the exercise in the link below. The G is first played as a just major third to an E-flat (=14 cents flat). Then the bass note changes and it becomes the just minor third to E-natural (=16 cents sharp). The difference you have traveled is 30 cents, almost a sixth-tone! You get a feel for these sixth tones, double that, you’ve got third tones and you’re off!

But why do these exercises? After all, I do not propose that thirds and sixths should always be tuned justly. There are many times when it makes sense to tune these intervals using equal temperment, such as when playing with any fixed pitch instrument. (I wish conductors would also take this seriously. How many times have you worked on intonation during a wind sectional rehearsal, when your ears will naturally drift to just intonation, only to have it completely different when you add the strings, harp, percussion or piano?) It also makes sense to play more temperately when you have the melodic line or when you want to make other expressive adjustments such as raising the leading tone.

Another place to avoid just intonation is when tuning minor thirds in minor chords (See Claudio’s comment below). Here, the equally-tempered minor third works better. Remember, if you tune an interval justly, the difference/combination tone you should hear will belong to (or complete) the implied major chord. For example, let’s take the minor chord:

G

E-flat

C

A justly-played C and E-flat will give you a difference tone A-flat, because A-flat is the major chord that the interval C – E-flat implies. That sounds very nice! But add the G and it’s no longer nice because G and A-flat are causing dissonance. This may be why, historically, those beautiful medieval works in minor keys always ended on major chords. See what you can learn about Early Music by delving into the details of intonation! The practices were practical, not academic.

While playing this exercise, it will also become apparent why, historically, notes with flats were generally played sharper and notes with sharps were generally played flatter.

Directions for playing with a tuner: during the fermatas, change the pitch of the tuner with the right hand while holding the flute (or piccolo) with the left hand only (use B-flat thumb for Bb and A#). Try not to interrupt playing during this process so you can make the adjustment as finely as possible.

Click here for the exercise – this is a compendium of exercises, the one with thirds and sixths starts on the sixth page.