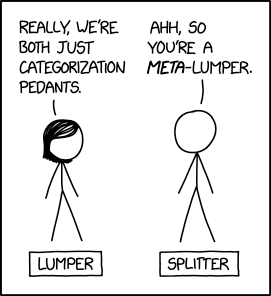

In the realm of notation of extended techniques, the phenomenon of Lumpers and Splitters is alive and well. First, a short explanation of this phenomenon, then I will give you my take on how lumpers and lumping seems to be the dominant force behind recent notation trends. In Part 2 I will discuss where I think lumping makes sense, and where it doesn’t.

The first known use of this term is attributed to Charles Darwin, and is defined by Wikipedia as “opposing factions in any discipline that has to place individual examples into rigorously defined categories.” Continuing with the Wikipedia definition, a “lumper” is a person who assigns examples broadly, assuming that differences are not as important as signature similarities. A “splitter” is one who makes precise definitions, and creates new categories to classify samples that differ in key ways.” I first came across this term while reading about the findings of hominin fossils in East Africa. Do the collections of fossils represent one species, or several? A lumper would say one species, a splitter would say many.

In fields where there is only a very small sample size, or there is little objective, material criteria, such as (historical) linguistics, religion, software engineering, you will find these discussions. Among musicologists, there are lumpers and splitters who debate on the periodization of our (Western) musical history.

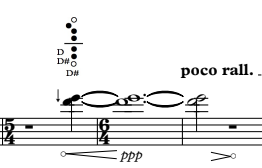

I am seeing a definite tendency towards lumping in the notation of extended techniques: using the term jet whistle to refer to diverse air/aeolian sounds, referring to multiphonics as split tones (no pun intended!), or all sorts of pizzicati referred to as slaps.

As to why there is this trend, “splits can be lumped more easily than lumps can be split” is perhaps the simplest explanation. And we all know that the more information that is out there, the less overview there is, and fewer people will take the time to try to navigate it. Therefore, the lowest common denominator prevails.

In my practice, I think it makes sense to lump some techniques, whereas other techniques could be more effective if they were subject to more differentiation.

More about that in Part 2.