With two performances behind me, I thought I would jot down a few notes on A Pierre. Dell’azzurro silenzio, inquietum by Luigi Nono. This is a “notes to self” for my future performances, but I hope they shed some light on some questions for other performers as well. These comments pertain primarily to the flute part.

I won’t go into the background of the piece, instead, I will direct you to Daniel Agi’s helpful article and table of multiphonics for performing this work on a C bass flute. Here is a share version of the full article. I also recommend reading the “Notes on the text” by André Richard and Marco Mazzolini found in the score. Another interesting read is an article by Laura Zattra et al “Studying Luigi Nono’s A Pierre“.

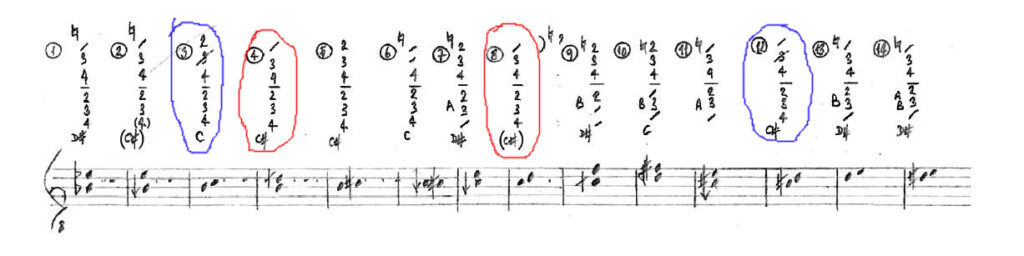

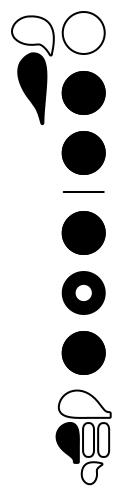

The part of the score that elicits the most questions for flutists is the indication for whistling (fischio). Roberto Fabricciani, Nono’s flutist collaborator in this work, whistles through his teeth; this is the method that can best combine whistle sounds and the resonance of the flute. I would prefer whistling this way if I could. Despite my efforts, I can’t reliably control the pitch with this way. Since the score indicates exact pitches (although the octaves can be adjusted to your whistle range), I whistle through the lips.

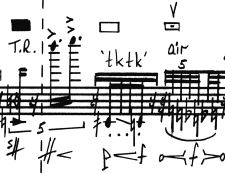

It’s important to know that the notation can be misleading in that it shows long, held sounds. However, the “Notes on the text”, found in the score, make it clear that every note should actually be in flux: multiphonics need not be entirely stable, fischio sections should fluctuate between the flute sound and the whistles (except where specifically noted that the whistle should be held out). This is also confirmed by a conversation with clarinetist Ernesto Molinari, who appears on the SWR recording with Fabricciani. The transitions from flute sound to whistling are very important. This is in no way reflected in the notation, but it is very important. Do not think that you need to learn a special technique of playing and whistling at the same time. It’s nice if you can keep the resonance of the flute while whistling, but it is the the transitions, the in- between sounds, that are most important.

If you know Nono’s Das Atmende Klarsein, you will be familiar with the technique of whistling and playing with the resonance of the flute. In my opinion, this is a different use of the effect from what Nono wants in A Pierre. In Das Atmende Klarsein, there are melodic and harmonic considerations that argue for the whistling and the flute resonance to be as steady and balanced as possible, whereas in A Pierre, they should be elegantly unsteady.

It has now become quite common to play A Pierre on a bass flute in C. There is no published score for this instrumentation; one has to take the original and make the transposition. At some point though, I want to try this piece on the instrument for which it was conceived, a narrow-bored contrabass flute in G. (There are very few of them in existence. See Daniel Agi’s article linked above). My suspicion is that this instrument produces fewer higher partials than modern bass flutes in C, which often have embouchure holes with high walls and a sharp blowing edge so that they can project in ensemble situations. These high partials are taken up by the electronics, especially the band-pass filters, and amplified. I don’t think this sounds terrible, but I wonder if Nono had used these modern instruments in his experiments, he might have chosen different parameters for the filter’s cut-off frequencies and different transpositions for the harmonizers?

Ernesto Molinari also said that the original idea is to have the players seated, not standing. I seem to have a vague recollection of a photo from the original performance with the players seated on stools that looked like contrabass stools. He also said the work should not go on for too long, never more than 10 minutes. For me personally, I think feels correct: this work is a small puzzle of a present for Pierre Boulez, almost jewel-like, and not a zoned-out, meditative work, despite its trippy, hallucinogenic sound world.

Also, keeping to the original timing (without being metronomically, robotically strict) does create a proper coinciding of the delay lines with the fermatas. According to Juan Parra, with whom we performed the electronics – theoretically, during the fermatas, Nono has calculated an event in the past that should be heard in the delay during the fermata. The fermatas are there not only as points of meeting for the players, but for the electronics to play out their parts as well. This is why they are given specific durations. The delay lines are also specifically chosen at 12 and 2 x 12 (24) seconds long for important psychoacoustic reasons. According to experiments Nono and his team did in the electronic studio, twenty-four seconds is approximately the time in which most people do not hear a musically repeated idea as a repetition, but as an independent idea.

I hope this is helpful to anyone working on this piece, including my future self 🙂