This is more of a public diary entry and notes-to-self than any sort of attempt to give tips or tools. Also, I attempt to sort out my thoughts of how things have changed in Darmstadt since the late 90s.

It’s been a few days since I premiered Georges Aperghis’ fascinating and wonderful The Dong with the Luminous Nose, and I am tired of mental postmortem self-criticisms that keep bubbling up into my consciousness. I need head-space for my next projects!

This piece really should be played from memory. The fact that my main achievement of the evening is I didn’t f-up the page turns with my page flipper is a testimony to that. And that the batteries didn’t run out. The list of why I didn’t play from memory is a long one – the final version of the piece was set 3 weeks before, and in that time period I had an opera to play, a family to have a kind of summer vacation with, and very time-consuming hobbies.

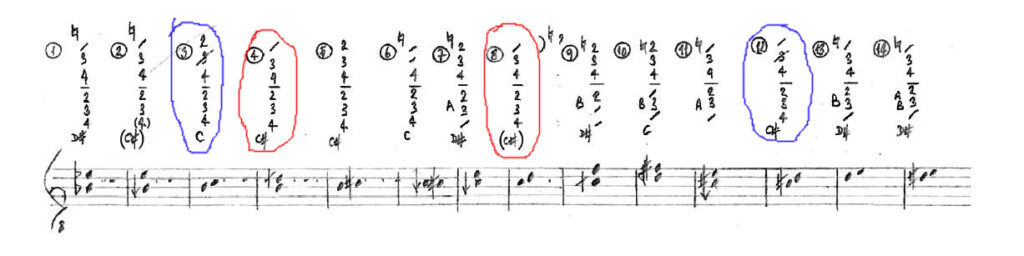

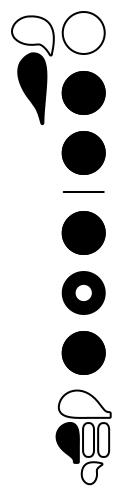

I was glad that there was a quality video recording, but am also happy that the recording is being removed from YouTube today, because although as a performance it was ok, I don’t want it to be the “definitive” version of the piece. Although that is a kind of joke. Little of the dramatic actions, voices, costume, that I did is actually in the score, so there never was and never will be a “definitive” version. There are no indications of how gestures are to be performed, the piece also has only two dynamic indications. For me, this is poses a very interesting interpretive situation, and has many parallels to my study and engagement with electronic music composition. Like electronic music, music that involves declamation of spoken text, a mixture of spoken text with instrumental sounds and dramatic gestures, cannot be prescribed with conventional musical notation. It puts performance, and not the written score, at its center. (Watch this documentary about Aperghis and musical theater if you want to know more about his esthetic.)

This situation for me was interesting because I gave the premiere in Darmstadt, where composition, composers and the “text” of music, i.e., the score, have historically been the focus of attention and resources. When I first attended in the 90s, I was struck by the hegemony of composers there, and their dominance, along with big-name festival organizers, in the whole contemporary music scene. There were very few composer-performers as role models in Darmstadt at that time (Markus Stockhausen was one exception), and the concept of composer-performer or improviser was neither thematized, promoted, nor rewarded. I was even advised there by a local composer to “stay away from the improv scene”, those players were really considered lame. This has changed, and I think this normalization is due to rapidly evolving technology and the emerging inclusiveness that is the result of successful activism and increased “woke-ness” by our cultural power structures.

As pointed out in Live Electronic Music, Composition, Performance, Study, our music history is written “from the perspective of the composer and rarely from that of the performer. Compositional outcomes have been the backbone of music historiography since it began in the 19th century”. This book examines questions of musical texts that are “nonexistent, incomplete, insufficiently precise or transmitted in a nontraditional format” from many perspectives (that of composer, performer, audio engineer to name a few). Historically, it makes sense that anything that leaves a paper trail (a score) will become a source for academics to pour over. We love artifacts. They provide a basis for taxonomies, give credibility, establish lineages, give credence to ideas. Since recording technology has developed, we have now another fixed source, that of recorded performances, over which to pour. This has “…opened up new perspectives, which have contributed to the revitalization of the performer’s role and the concept of music as performance.” I love this book!

Now is the time for composer/performers, improvisers, and those who work with media whose sounds cannot be codified/”textified” by a score, to assume more prominence in our Western music history and the power structures that determine our cultural life.