The following are suggestions for practice in preparation for the flute and piccolo passages of (my favorite ensemble piece!) the Ligeti Piano Concerto. They are my own ideas, not authentic or especially original – except for one remark on the piccolo solo in the second movement that Ligeti gave me during the recording session with the ASKO Ensemble and Pierre-Laurent Aimard. I am also writing this for myself, should I lose my notes.

The following are suggestions for practice in preparation for the flute and piccolo passages of (my favorite ensemble piece!) the Ligeti Piano Concerto. They are my own ideas, not authentic or especially original – except for one remark on the piccolo solo in the second movement that Ligeti gave me during the recording session with the ASKO Ensemble and Pierre-Laurent Aimard. I am also writing this for myself, should I lose my notes.

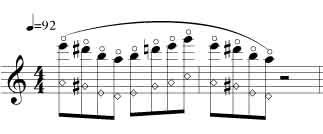

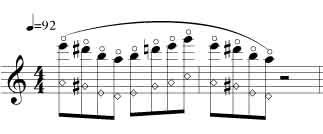

The harmonics in the first passage I finger an octave and a fifth below, mostly. The notes above G# I use special fingerings, not “real” harmonics. (See my entry When Is a Harmonic Not a Harmonic?) I give no fingerings for these notes, because they change from performance to performance, depending on the intonation of my colleagues and my own condition. In spite of the cross-rhythm going on, these passages should be played smoothly and evenly. I like to practice them like this:

The piccolo solo at “O”, though marked poco leggiero, should not be played staccato, the eighths should sound full. The lightness is in the rhythmic inflection.

In the second movement at “A”, Ligeti told me to forget the rests, the eighth notes should be longer than notated. I play this passage with very little vibrato, although this is a personal decision. Ligeti had no opinion on the matter. My goal is that the listener should not really know what instrument is playing – just some sort of haunting sound similar to the ocarinas that come in later. It is good not to play too quietly before the bassoon entry. The bassoon enters in its altissimo register, and can be very difficult to control.

In the third movement, the harmonics at “M” I finger two octaves below. For the high A, I add the G# key, and for that high B at 2 bars before “N”, I don’t play a harmonic – just use the normal fingering.

In the fourth movement after “Y” the texture becomes very complex due to several rhythmic layers. You have eighth-note triplet movement (always with displaced accents in groups of 2 or 3) and sixteenth-note movement (always in accented groups of 2 or 3). The base tempo is quarter-note = 138, so I like to play around shifting between regular triplets at this speed, then playing the sixteenth note passages that have accents in groups of 3 as triplets, but at tempo 184. For example, the second bar of “Y”, starting the third beat, would look like this in my exercise:

There are two clarifications to the part: 1)”DD”, the third note (A) should be a sixteenth-note. 2)There should be a rallentando from “EE”.

The fifth movement has That Lick at “C”. I find it useful to keep the C key down for the whole thing, even the beginning, since I have a B-foot. That works better than the gizmo-key in this situation, for me. I also leave out the trill key on the high B-flats, and use the following harmonics to facilitate fingering:

An important note on the rhythm. The time signatures in this piece function as a grid on which many networks of cross rhythms are laid. Therefore, in the indivudual parts, it is important to not interpret the rhythms in a traditional agogic manner; that is, with stronger beats on the 1 and 3, weaker beats on the 2 and 4. In other words, there is no traditional hierarchy of beats within a measure. Ligeti has carefully written accents where they should be. In light of this, it is also important that synchopations are not played as synchopations (with a playful “kick” on the off-beat). Your off-beat might not be an off-beat in the grand scheme of cross rhythms.

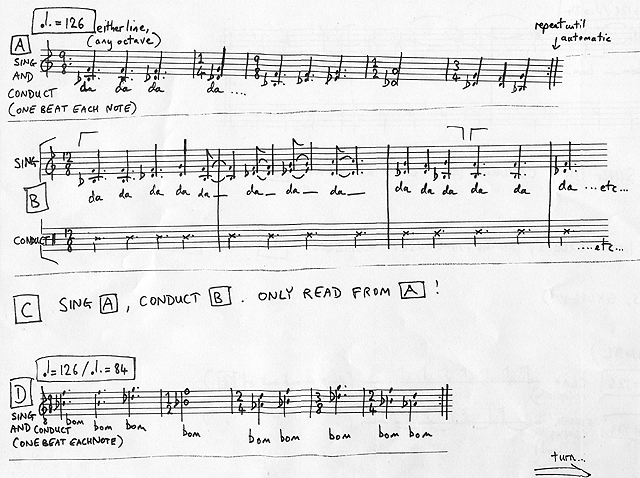

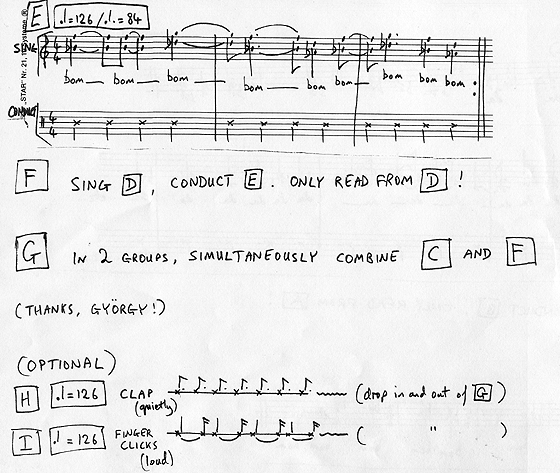

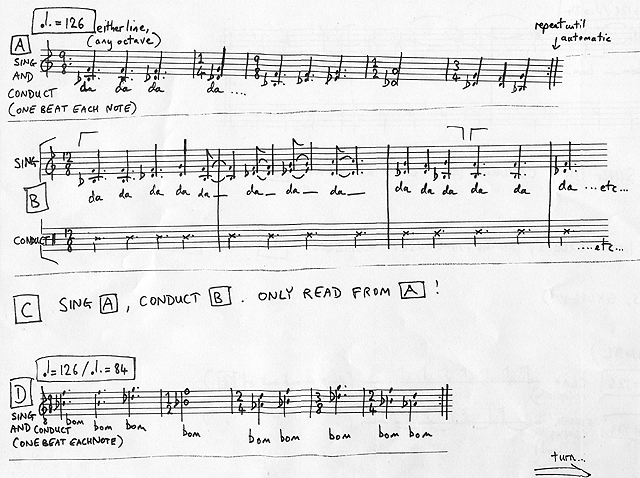

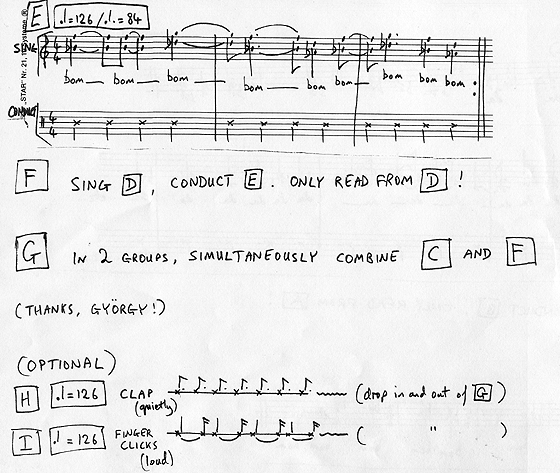

Clement Power, who will be conducting our next performance with Ensemble Musikfabrik on April 19th, has come up with the following exercises based on the opening of the piece, which I find quite useful:

I’d be curious about other’s experience with this piece, so please feel free to comment.