In my last entry, I made some sarcastic remarks about the tempo in Berio’s Sequenza for flute being too fast. Now with genuine curiosity, I would like to probe composers’ psyche in the hopes that it will reveal why given tempi are often too fast. I will try not to make this a rant.

Given today’s technology, it is not surprising that computer generated scores can churn out notes at a certain tempo that sounds “correct” when electronically reproduced. Then when produced with actual living, breathing creatures playing mechanical objects, the composer realizes that compromises or adjustments to tempo have to be made. That is understandable. However, I encounter this phenomenon with pre-technological pieces as well as contemporary ones that were composed away from the computer.

The problems I see when a tempo is too fast:

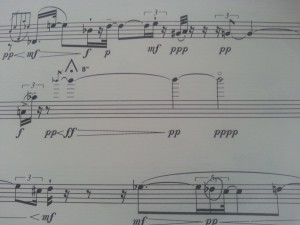

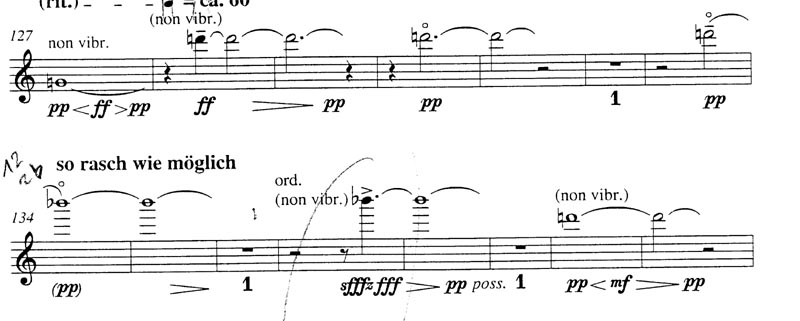

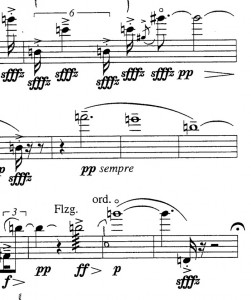

- Variations in division of the beat are poorly perceivable. Personally, I like my quintuplets to sound like quintuplets, and be discernible from sextuplets or sixteenth-notes.

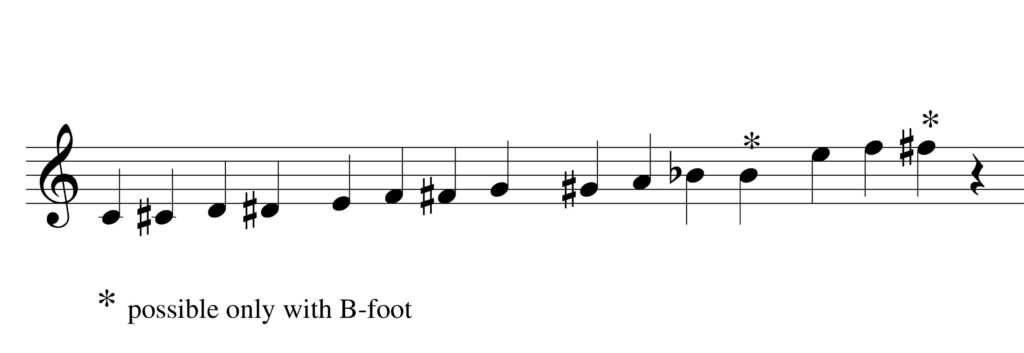

- Variations in pitch are poorly perceivable. Not only are fingering and lipping microtones difficult at high speeds, but can you really tell in a blur of notes if I play an F or an F a sixth-tone high? Should I really bother? [When I (and probably most flute players) get excited about a loud, fast passage, my F, and all the surrounding notes, will be a sixth tone higher whether I like it or not.]

- Variations in articulation are poorly perceivable. If inflections of long and short are important, I would appreciate time to produce them and to make sure the audience has time to capture them.

Sometimes I am annoyed when I point out these things to a composer, and the response is: “Oh, that is the tempo you strive for, the ideal tempo.” Well, do I really strive for that tempo (which I can achieve in some cases) and sacrifice the musical details? If you know me already from reading my blog, I am at my worst when presented with conflicting information. I do appreciate conflict as a positive creative force, but do not appreciate it when it is a result of artistic laziness.

But I am a nice person, and cannot believe that the majority of composers are lazy. So what is going on?