Some musings on current and future collaborations:

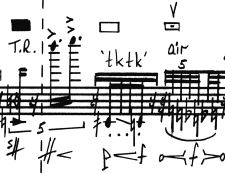

Yesterday I discovered a new sound on my bass flute. It is high-pitched and horrible and usually something that I try to avoid. But like some things, under magnification or extreme pressure, it can yield a diamond-like beauty.

I discovered this sound during my first session with composer Javier Vázquez, who is composing a duo for flute and percussion to be premiered with Dirk Rothbrust (probably via video) in June. In our session, I attempted to imaginatively sonify different urban environments – the area around Cologne Cathedral, train station and the Rhine. To be honest, the Rhine kinda scares the crap out of me. Its volume is way too much for the narrow channel it flows through. It flows so fast that in the past, after barge crashes, some containers never get found. They are driven into the river bottom by the current, I guess. Imagine not being able to find something the size of an 18-wheeler. Anyway, this is what I was thinking about during the improvisation and made that horrible but potentially useful sound.

Another collaboration that has evoked new sounds has been with the composer Tomasz Prasqual, who is writing a duo for flute and Moog synthesizer to be performed with Uli Löffler in May 2022. We have had many Zoom sessions in which while improvising I get so lost in the sound that afterwards, I have no recollection of what I just played. This probably happens to many of us who do this :). Tomasz and I have both have Moogs (mine is a VST) and it has been great getting to know a new instrument. Really, really looking forward to this piece.

I opened a can or worms with Georges Aperghis, when I told him I wanted a piccolo piece and liked the works of Edward Lear. Now I have to figure out how to sing higher than anyone wants to hear me, and recite the most bizarre text with a kind of straight face (well, straight enough to keep playing the piccolo). I am wondering about “The Dong“, its phallic implications and allusions to interracial love (after all, what else are the Jumbly Girls with their blue skin and green hair?). Hopefully, the premiere will go ahead as planned in Darmstadt this summer.

Many years ago, I approached filmmaker Guy Maddin and asked him if he would make a silent film for us at Musikfabrik, loosely or closely based on themes from Daniil Kharms‘ life and works. He agreed and with the support of the Acht Brücken Festival in May, we will perform (again, online) two commissioned works by Nina Šenk and Anthony Cheung to the film “Stump the Guesser”. Although I haven’t collaborated with the composers, I am chuffed (as the English would say) that a spark of one of my ideas lead to a working relationship with this awesome filmmaker!

I have been trying my own hand at putting music to film, and am pleased to announce that last Fall I won a social media challenge for my film trailer to the (then) new Star Wars film. (Made with many flute sounds!) While researching film music for this challenge, I was appalled by the musical lack of experimentation in mainstream sci-fi. To those already in the field, I am sure this is a “known bug”. But seriously, people are projecting orchestral sounds from the 18th and 19th centuries on to scenes which should be taking place in future centuries! Where is the imagination in that? Of course there are many cool exceptions, but it’s time to move on, people.

Last but not least, next week I am doing a remake of Ole Hübner’s “This place” for solo flute and layered video. Normally I don’t like pieces that deconstruct or make use of direct citation, but Ole has really rocked Dufay’s Nuper rosarum flores, and I am majorly challenged with gnarly bass flute harmonics, multiphonics and circular breathing. What more could a flutist want?