This is the first of a series about practicing complex rhythms related to a pulse, a.k.a. polyrhythms.

Why bother practicing polyrhythms? Some of us have been taught that our metronome is our best friend, but how useful is it really? Do we bother to listen to it? If we do, does it ensure us a good sense of rhythm? If some of us were honest, we would admit that we do not want to listen too closely, for fear of being labeled mechanical. After all, we want to play rhythmically, not mechanically. How to do this?

What I suggest is a method to develop rhythmical phrasing through the study of Taffanel/Gaubert’s study no. 1 from Exercices Journaliers. (I choose this because most of you reading this are flutists, and it is best to apply these ideas to something that is already familiar.). But this introduction will first cover the basics.

A well developed sense of rhythmical phrasing can help whether you want to become the next star beat-boxer or want to keep a steady Scherzo from Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

You will need a metronome that can be set to a simple beat pattern (2/4, 3/4, etc.), and a willingness to feel a bit clumsy at first.

The following examples use simple mathematics to see visually where your pulse is against the metronome’s (or your partner’s). It is a graphical guide to help develop a FEEL for the polyrhythm.

Given polyrhythm a:b, where b = metronome beats and a = your beats, there are two ways of figuring it out:

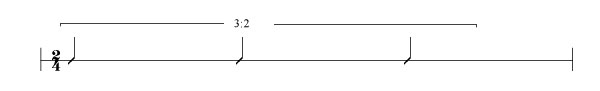

1) Take the b number of metronome beats and divide it into units of a, then clap or play every b number of these units. Let’s take the example where a:b = 3:2(three against two). In standard notation it looks like this:

_____________________________________________________________________________

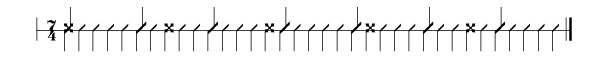

2) The second way to figure a:b is to multiply a times b, in this case 3 times 2. This gives us six:

Now divide this 6 into a (3). That gives us two, so mark every two pulses with an O on top. Then divide 6 into b(2) . This gives us 3, so marks every 3 pulses with an X on the bottom.

The “O”s are the rhythm you play or clap, the “X”s are the metronome beats.

Here is a more complicated example: 5:7

Leave a Reply