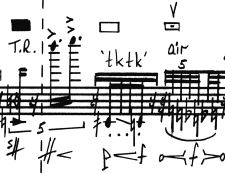

In Bite for solo bass flute, Rebecca Saunders attempts a special synthesis of speech and bass flute sound that I have not encountered in the repertoire so far. Unlike most works that use the voice and the flute, the voice is not relegated to a singing or narrating role. The phonemes of speech are used to shape elements of the flute sound, much like an ADSR envelope shapes the amplitude and filter of a synthesizer’s oscillator. This what I call speech-gesture language was developed during our work on her ensemble piece Stasis. In Stasis, I was given a text from Samuel Beckett and had quite a lot of freedom to put words to various palettes of multiphonics or other sounds, forcing each word into a sound.

In Bite there is no such

freedom, it is a thoroughly composed work and all the speech-gesture

language has found its way into the notation. No clearly spoken text

can be heard.* A performer does have the freedom, however, to add

text if it helps to shape a phrase or even a single sound. Some text

I added found its way into the printed version.

My only other interference

in the compositional process had to do with the editing. The first

draft lasted about 19 minutes, we brought it down to about 13 for

this final version. I pleaded for one section not to be cut, because

I particularly liked playing it.

Aside from learning the

notes, I had several particular challenges in learning this piece.

The first was the physical challenge. Since my bass flute is

particularly heavy I had to buy a special stand to take the strain

off my wrists and elbows. The work is also quite cathartic, sometimes

one is required to shout or loudly vocalize with fluttertounge. This

is something I enjoy, but I had to take care not to strain my voice

during hours of practice.

There were plenty of

artistic challenges for me as well. The work is interesting in its

contrasts. Spectrally, one goes quickly from very rich, saturated

sounds to very détimbré sounds, from over-blown rock ‘n’ roll

sounds to the finest multiphonics. That in itself is technically

difficult. In addition, all sounds are introduced in the first three

minutes of the work. Since sonically nothing really new is

introduced, I have to somehow generate my own flow of energy to

engage the listener for the remaining ten minutes. This energy and

engagement is musically very important because there is no

development or narrative (which I find amusing in a piece which uses

elements of speech).

I think this is one of the

brilliant aspects of Rebecca’s music. Its modular components allow

one to color their own interpretation with their own spectral and

dynamic palettes. Indeed, one is forced to do so, because one can’t

rely on traditional forms or gestures to carry the music. This opens

up the path to contemplate and develop other aspects of musicianship.

I hope in these endeavors I succeed somewhat, and curious listeners will enjoy this recording. It took place after several years of performing it in concert, so I had plenty of time to let the interpretation mature. Yet each time I look at it anew, I always make discoveries!

The score is available through Peters Edition. If you have a library copy, check to see if that copy matches the latest Peters Edition version. There are quite a few differences.

*This is a great contrast to the piece I am working on now by Georges Aperghis for solo piccolo/narrator “The Dong” based on text by Edward Lear, which will be premiered in Musikfabrik’s concert in Darmstadt hopefully August 7th, 2021.