This text has been adapted from introductions to my presentation to student composers on writing for flute that I have given the last few years. The actual presentation is here.

I’d like to start with a short preface about some general ideas not specific to the flute, and to preface: what I am about to say you can easily ignore if you are writing a solo piece for a particular player. But to successfully work as a composer with an ensemble or orchestra filled with professional, experienced, perhaps middle-aged and grumpy players, I suggest you pay attention.

I have reservations about giving these kinds of information-dump talks these days. You don’t really need me here, most of this stuff you can find on YouTube. However, information is not knowledge, and as a teacher I want to impart and share knowledge. That is why I will try to focus on concepts, because as adult learners, that is what we really retain.

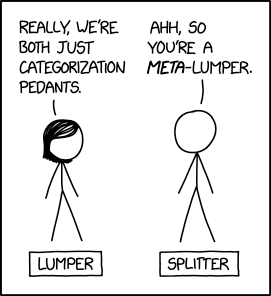

Maybe you have heard us players complain that “instrumentation has become a lost art”. I used to think that, but now I think that is somehow romanticized. Perhaps what we are observing is the nature of evolving systems. As in other systems, such as computer programming and software development, some aspects of the work flow become trivial. In the scope of musical composition, instrumentation has become trivial.

Let me explain. In our society, and in your degree program, you are under pressure to get started and produce right away. So it is expedient to know what knowledge is trivial and what is not. What is not trivial is fundamental; an example of that is the need to know which clef for which instruments, which transposition for which instrument. Just as when learning a computer language quickly, you first learn to print “hello world!” and you need to know how to type the syntax and whether to put a comma, semicolon or whatever at the end of your statements. But beyond that, more specific things (like the code for a fluid dynamic simulation or a how to notate a string or woodwind harmonic) can be looked up and then memorized as it becomes part of your routine. In other words, you don’t have to carry around tons of information in order to get started and get productive. This is what I mean by an evolved system, they tend to have streamlined and rapid work flows. Whether it is a short-lived or long-lived system remains to be seen.

So as I give this presentation, think about what might be fundamental or trivial for you. I will try to underline basic concepts (like acoustical constraints, which you can see from the design of the flute) that I hope you will, if not at least retain, at least remember that this is something you need to check the docs before diving into 🙂 And I will send the link to this presentation for your reference.

In this presentation, I will also try to walk the line of what is necessary for players to read and what will not stifle your creativity. Most of us here at Musikfabrik also do not want to contribute to the culture that is only going to produce sight-readable, boring pieces. At the same time, I want to keep you from making the same mistakes over and over that make players loose faith in your process. If you think about it, would you take a text seriously if it were filled with spelling and punctuation mistakes? That might be acceptable in poetry, if done deliberately for artistic effect. But for that, I would suggest a graphic score 🙂

Speaking of scores, as a final note, I would like to introduce a novel concept that I think should be adopted by all composers, and that is to put your scores (maybe) and parts (definitely) in some sort of GIT version control system. Not only would it be helpful to keep track of different versions, but would also allow community contributions, corrections, improvements, etc. For instrumental parts this would be super! For example, I could suggest fingerings, and that version would automatically be saved for the next player, who might alter them and create their own version, and future players could examine both versions and contribute or correct to make their own. Nothing is erased or thrown away, and the process can be viewed at all stages.

Producing artworks is often teamwork, creativity takes all kinds of knowledge and contributions. No longer are you as composers expected to be lone geniuses who toil in solitary towers, so there should be no shame in allowing players to access your parts and make them playable in their own way and then share them back to the community. This would put publishing houses in trouble, though.