On forums and in masterclasses there has been a lot of discussion about which element plays a more important role in producing intervals on the flute. Aside from the change of fingering, do we change more with the lips, with the air speed, or with air volume?

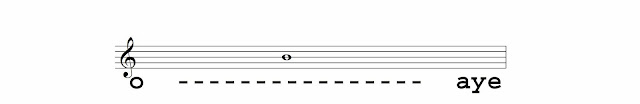

Take the fingering element out of the equation and try playing through the harmonic series on low C or D. How do you produce the upper partials?

The trend these days is to say the air makes the changes. Emily Beynon makes a good example and case for air speed:

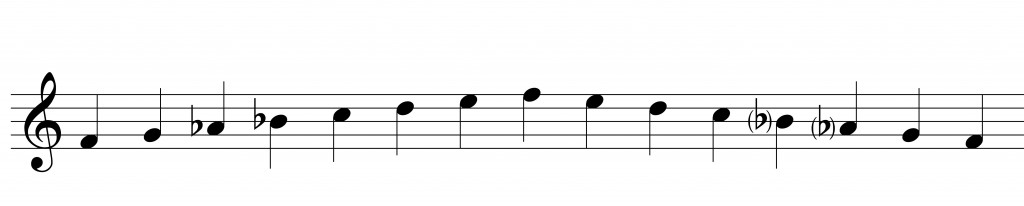

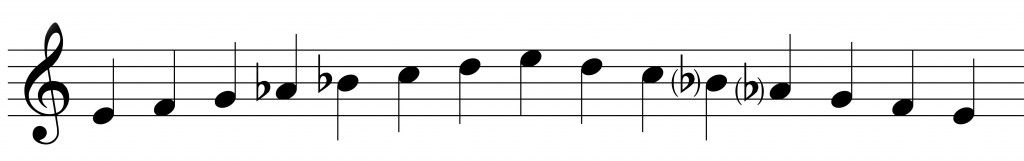

In this (long) masterclass series, Phillipe Bernold has a student start the day on a rising dominant 7 chord. Here he suggests the most important thing to start the day is to wake up the air column. There should be a natural increase of both volume and speed of air as you ascend. The lips stay neutral. This is very important for legato.

Here is why I agree that the air, either volume or speed, rather than the lips should play the major role in interval moving. Please note I do not deny that the lips must remain flexible, and that exercises for suppleness also include playing intervals and harmonics (at least some of mine do).

As humans, which is more necessary for survival, fast reflexes of our breathing apparatus, or of our facial muscles? Imagine a pre-historic flutist out strolling, searching for good material to build the perfect bone or wood flute. She is set upon by a leopard. She screams and runs. The lightning-quick reflexes of that sharp intake of breath to make sound and to get enough oxygen for the muscles to run is what saves her life. Fast-talking a leopard has been a known fail.

So it is my unscientific opinion that the muscles controlling the breathing apparatus, including the diaphragm, have much quicker reflexes, thus can make quicker adjustments than the facial muscles used in the embouchure. Of course, we all know some fast talkers, but they are a scientific law unto themselves!

Wildlife disclaimer: when stalked by a predator in real life, do not act like a prey animal and run. You will be chased. And caught. Unless they are bees.

Photo: bigkitten.com