[Taken with permission from an interview with Cássia Carrascoza Bomfim, in preparation for her doctoral dissertation]

Do you feel a lot of difference between playing works with a pre-recorded tape and computer processing in real time (Max/msp)?

Both ways present various issues of playing with a microphone. With a tape piece, I am concerned that the live sound mixes with the electronics. With computer processing, I have the additional concern to make sure I play in a way that my signal will be processed, which sometimes compromises variation in dynamics and articulation. For example while playing Nono’s Risonanze erranti with Musikfabrik, there is a measure where the piccolo is marked ppppp. However, if I play that dynamic as written, the signalisation will not register. If one has a standing microphone, then it is possible to play around with the distance between you and the microphone, but if you have a clip or contact microphone, this is not possible.

A pre-recorded tape piece may have the advantage of technological simplicity, and if it is well conceived, then it provides either freedom to allow asynchronicity or good cues (acoustic as well as notated) that facilitate synchronicity, and does not constrain the performer in terms of sound color and dynamic. A great fun, technologically simple piece I have played is David Dramm’s Thrash and Variations for Flute and Boom Box, where I just walk on stage with a portable CD player, and off I go! With real time processing, I feel artistically more free in terms of spontaneity of tempo, but have more worries because there are more things that can go wrong, i.e. program crash, more cables that can be defective, midi cables or an interface that can be defective. I don’t do the electronics myself and rely completely on my technician partner. So yes, I do feel differences.

In relation to your feelings of time and tempo, could you point out the differences between the two genres?

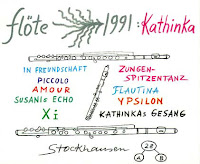

This is very dependant on the piece. Of course, there are tape pieces that offer you absolutely no freedom in terms of time, and in some cases I welcome a click track to help the coordination. There are some bars of Michel van der Aa‘s Rekindle that were challenging for me. This wonderful piece is cleverly done so you don’t generally need a click track, but there were a few bars at the end where there the flutist is only playing long notes and there is nothing going on in the tape part to give you a sense of pulse, so you really have to rely on your inner metronome to stay together. A piece like Stockhausen’s Paradies has an unmovable and inflexible tape part, but a click track is unnecessary because much freedom is given to the performer in terms of the tempo. (There is theoretically also freedom with the dynamics, but since the tape does not offer dynamic differences, the player is rarely given an opportunity to play really softly.)

With live processing pieces, there is sometimes freedom of timing, sometimes not. For example, Saariaho’s Noa Noa gives the performer, by means of a foot pedal, the means to choose timing. However, the samples and effects that are triggered have their own programmed time, so if you rush, the sample or effect will not play out, or if you are too slow, there is an unmusical gap. (This piece may also be played without foot pedal, with the sound engineer following the score and triggering the samples.)

Could you tell more about your experiences with click tracks?

With ensemble pieces, we often discuss if we should all have a click track or just the conductor (or if chamber music, just one of us). Not everybody translates the pulse of the click the same, some play more on the beat, others after, and we always argue about what kind of sound we should have for the first beat of the measure (high, low?) because depending on the tessatura of your instrument, it could make a big difference. So sometimes it’s more satisfying to play as chamber music, without a click track. A click also has to be well done and have helpful cues to alert us that we are coming up to a tutti or a new section or tempo change. Another issue is the division of the beat, or whether a beat is subdivided or not. We once played a piece that required a click track, but the click was extremely unhelpful because for the tutti sections, all divisions, even 32nd note triplets, were clicked! Such minutae is annoying rather than helpful since with a flurry of clicks, you can actually lose the sense of pulse. In general, it really depends on the individual piece and the quality of the click track, whether we decide to all have a click or follow someone with the click.

As a soloist I am happy to play with a click if it really helps. Recently I premiered Ole Hübner’s this place for solo bass flute, several layers of video and audio together (watch on YouTube here). When playing a coordinated sound track, a click is extremely helpful. The question for us was from where to run the click track, to send it from the computer to my headphones via cable, wireless, or for me to play it from my own device? For simplicity’s sake, I played it from my own device, just giving a cue for the start so my click and the recordings would be together. This can be risky though, if the starting cue is not together.

With real time processing there are other factors to consider when using a click track. Sometimes there is a latency of the signal processing. Then I hope the effects and the acoustics hide any imperfections of synchronicity.

If you are lucky, you get the click track in time to practice with it, especially if there are these sort of compensations that have to be made. In our experience, if you have a click track, it is really important to practice with it and not spontaneously rely on it in concert.

Do you think as rule, that you are more free (in the time sense) playing with processing in real time than with a pre-recorded tape?

For me the only time I feel completely free from questions of time is during improvisation. This can be a lot of fun with live electronics, but also effective with tape as in the last movement of Nono’s Das Atmende Klarsein. Whether I feel free depends more on the composition and the composer’s conception (and notation) of time than the technology itself.