Almost didn’t get out of bed that day. I was under the weather, and a warm blanket, but I managed to hop on the train to Amsterdam in time for Ferneyhough’s seminar on his flute pieces, which was organized by Joel Bons (artistic director of the Nieuw Ensemble) and Harrie Starreveld.

Harrie kicked off by playing a bit of Mnemosyne for bass flute and tape (or- and this I’d forgotten – 9 live players. I’d just love to be part of that someday!). He discussed how he learned and practiced the piece. Nowadays, you can put the notes into the computer and play them back, at all speeds. This would function as a kind of mnemonic learning device for the rhythm, but only an additional device, you would still need a click track to stay together with the tape. Ferneyhough highly recommends using a click track. Some players have tried without and not succeeded. The problem with getting out of sync with the tape is that the harmonies, which play a crucial role, will be all wrong.

Harrie played a recording of a computer realization of one bar to show how one could slow it down to learn the rhythms mnemonically

To me, personally, this is an added human element to a performance of his music. This contemporary vernacular is yet-to-be defined, and seeking it is part of the creative process. Maybe this is also what he means by the performer observing his/herself learn?

Next our student Daisuke played Cassandra’s Dream Song. One part of the opening passage was the best Ferneyhough had heard it to date. Way to go Daisuke! The opening strophe Ferneyhough described thus: the first half is “effort rhythm” then “precise rhythm”. It is a building up of energies, a somatic crescendo, then releasing. This is to engage the body from the very first moment of the piece. The flute as an extension of the body is how he thinks of this piece.

I didn’t know that the original idea was to improvise the order of the strophes during performance. However, Ferneyhough has gotten away from this idea. One has to find a way to intersect the two pages and create chains of continuity.

He touched on several of the techniques, the different vibrati/smorzato, and the section with voice. A male flutist should, ideally, sing falsetto. If not possible, you need to add the beating effect, as this passage should sound like two weaving sine waves. He is not sure if the fingering of the multiphonic with the high F# is a good one. He didn’t have an open-holed flute to work with, so was wondering if someone would come up with a better fingering.

While discussing notation at one point he said: you don’t choose notation, it chooses you.

Then a brave lady [must find out name, anyone?] played Superscriptio. This turns out to be not the first piece with irrational meters (1/10, 3/12). It was first done by Henry Cowell, then by Dieter Schnebel in the 1950’s. (See also my post on irrational meters.)

He admits that the opening page and a half is cruel. However, that is not the intention. This piece opens his entire Carceri cycle: a single instrument – high and very light. The opening section is not meant to be “musical” – rather, it is coming to terms with ways of contrapuntal thinking. Later on, the material becomes “musical”. Harrie commented that the opening is however quite melodic, like a children’s ditty. He even performed it as such for a radio broadcast.

The next section needs attention to the speed of articulated passages. They are at uncomfortable speeds, sometimes slower than expected. This is important, otherwise one can get carried away and go with the vertige, but then it ends up sounding like any other contemporary piccolo piece.

There is a famous passage in this piece with repeated C’s that are notated differently, but performed at the same speed. This is because he has several systems running simultaneously. When things like this happen, OK. Even if his system comes up with something tonal like a reference to a major triad: so be it. The performer needs to be aware when this happening, but doesn’t need to show it to the audience.

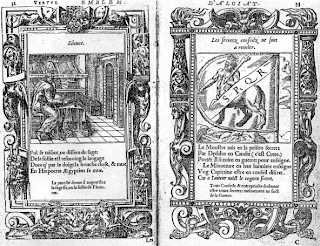

Further, he explained the meaning of the title “Superscriptio”. It’s part of an emblem (usually found in collections called emblem books). This was a 16th century form of learned entertainment – a combination of texts and images . Above the image a short motto (lemma, inscriptio [superscriptio – because it is above] ) is scratched or handwritten introducing the theme or subject, which is symbolically bodied in the picture itself (icon, pictura); the picture is then described and elucidated by an epigram ( subscriptio ) or short prose text.

Leave a Reply