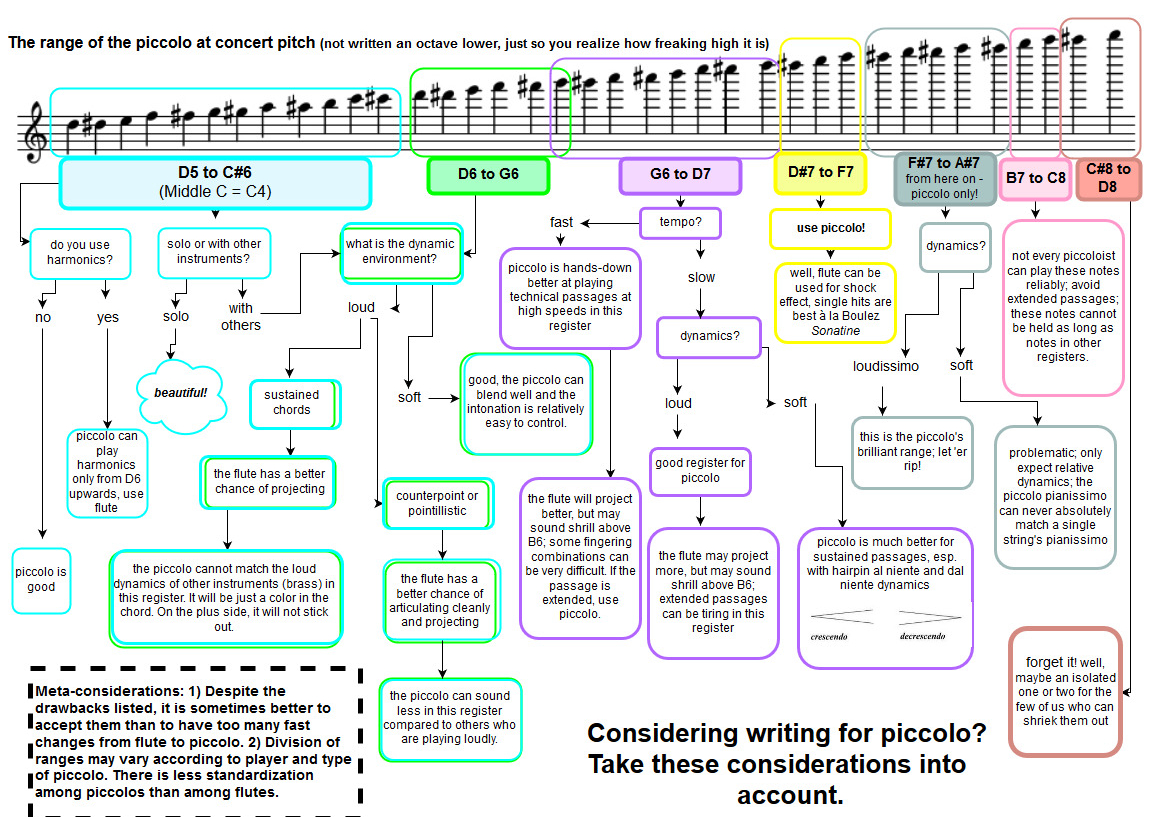

It is still a work in progress, but here is a flow chart to help composers familiarize themselves with the characteristics of the piccolo. As with most of my advice, it is applicable mostly to ensemble writing – with solo works one has a lot more freedom.

Author: admin

-

Getting Back in the Saddle

I noticed a strange thing about getting back in shape after the last winter break. I was frustrated and, to be honest, a little frightened at how long it took to retrieve my “norm”, and wondered if it was a dire sign of things to come. I decided to blog about it, not only because most of us have a winter break before us, but to find out if I am the only person to have come up with the solution that I did.

My problem was sound, so I worked on all the “sound” things I was taught. Sonority, harmonics, melodies, whatever I could think of. Even articulation exercises, as sometimes if I do some forward tonguing, my lips are really encouraged to focus and relax. But that didn’t really help. Nothing seemed to really get the fuzz out. However, after a week or so (yes, it was that long!) I decided to ignore my sound and at least not let my fingers lose their condition as well. So I worked slowly on 2nd and 3rd octave chromatic exercises (from P. Edmund Davies’ book) and strangely enough, focusing on really coordinating my fingers somehow got my mouth to do what it had to do to get a good sound, and ping! I could play with my normal sound again.

Today*, due to delayed travels and chaos, I picked up the flute for the first time in a few days. Same yuckiness, but I remembered last year’s trick and it worked again. Was it my imagination, or could I actually feel the neural network involved in coordinating complex fingering activity actually communicating with and instructing my breathing apparatus and embouchure network on how to make an optimal sound? That is really what it felt like. Is there some neurological explanation for this, or is it psychological?

*Actually today is Christmas day for many, but here in Russia, it is just another Monday.

-

Pierre Boulez Dialogue de l’Ombre Double for flute/bass flute

Adapting, recording and releasing the flute/bass flute version of Boulez’ Dialogue de l’Ombre Double has been a ten year labor of love (and frustration). The mischievous flutist inside me listened to this clarinet piece and thought, why doesn’t Boulez write for flute this way? Not to disparage his wonderful works for flute, but his Dialogue has such contrasting characters who are so articulate and moving in ways that his flute characters are not.

In 2007 I received permission from Boulez to attempt a version. After completing the score and several performances, the version never received acknowledgement, but it received no prohibition, which I took as an OK to continue. Now the necessary permissions have been received for the recording, which I am proud to announce is available here:

Pierre Boulez, Dialogue de l’ombre double, version for flute and bass flute

The score is not available commercially. Please contact me if you are interested in taking a look at it. It has not been fully edited, there are some odd enharmonic spellings of notes due to transposition.

Some comments about the flute/bass flute version: I originally wanted to make a version for just the bass flute. While I think this may be technically possible, I was too frustrated by the instability of the intonation of the upper register. Maybe on today’s bass flutes, with narrower bores, this would be less of a problem. The bass flute has also less scope for dynamics than the clarinet. This is not surprising, clarinet making and performers have had generations to develop their art. Bass flute making and playing is still in its early generations – although Eva Kingma and Kotato are making wonderful headway. So I decided to switch from flute to bass flute between movements (although I attempted to do so in a way that is not monotonously predictable, I hope) in order to play in tune and to emphasize the changes of character.

I would like to take the opportunity here to thank Melvyn Poore, who recorded the initial, final, and the transitions, and performed the electronic parts in concert with me. He also made the recording which is now available. Thanks also to Hendrik Manook who did the final mastering. A big thank you to Mark Steinhäuser, who transcribed and transposed the score for me.

-

Berio Sequenza Audio Recording and Saunders Bite

Some time ago I posted about recording the Berio Sequenza for Flute. So many other projects have been realized since our session in January 2016 that there has been a large gap between recording and release, but we have made sure the recording is decent. I have only the following reservations: since the idea was to produce a video, I did my best to perform from memory with large takes. While that may make for a better performance, the audio does have some issues of timing; some passages could have been more accurate regarding speed and length, had I been looking at the score. The video has not been issued yet, but I hope that when it comes out it will offset my disquiet. (Although watching oneself opens another can of worms.)

The recording is available through the Musikfabrik Label, which is a digital platform that offers multiple download choices – please browse the catalogue, you might find other recordings that interest you! Here is the link.

My next big recording project will probably not take place until 2019, when I plan to record Rebecca Saunders’ Bite for bass flute. I have performed the piece several times, and have no exclusivity. So if you are interested in a massive, expressive, sighing, ranting piece for bass flute with low B [edit: now there is a C-foot version.], please check it out! If you have a library copy, please check your version against the final version sold by Peters Edition. Some earlier versions started circulating before the final one, and there are significant changes.

-

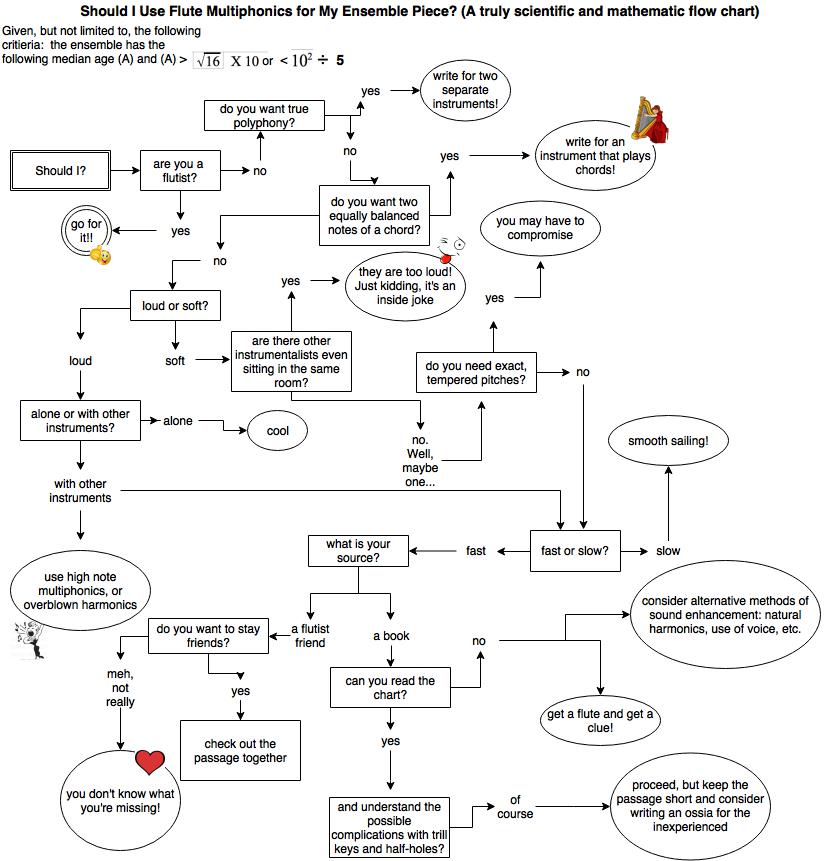

Multiphonics, yes or no. A Flowchart

Well, it’s more of a labyrinth than a flow chart, but here it is. This is specifically geared towards ensemble writing. Here’s a link to the file as a PDF: Multiphonic_flow(3)

-

Preparation – again

For me there are still three levels to gain once you have practiced a piece.

First, you can read it through

Second, you can actually play it

Third, you can start to make music with itNext week I will play the premiere of Rebecca Saunder’s Bite which is a 15+ minute piece for bass flute solo. If I am lucky, I will reach the third level. Watch this space, I would really like to write about it. I just hope I find time before the year is over.

-

Seasons, and a Practice Idea

I have been thinking about practicing freely and vacation time from the flute. In the past, I have put the flute down for long periods of time (8 weeks was my longest break, when I was juggling a big decision of where to settle down). However, despite my long vacation time this year I realized how much I enjoy vacation practice when the sun is warm and everyone is relaxed and enjoying themselves. I play a bit, go pick some raspberries, play some more, sit in the sun and read. It is a healthy rhythm that is denied to me under normal circumstances.

When the weather is cold or rainy (like most of the time where I live), I just want to be under a blanket curled up with a cup of tea. When temperatures climb over 20 Celsius (ca. 69 Fahrenheit), most of the people around me start complaining how warm it is, but that is when I come alive and want to actually accomplish something (maybe because I am a snake, according to the Chinese horoscope).

So I took breaks from the flute this summer, but only a few days at a time. Now I face the challenge of a new season with a dizzying amount of pieces to prepare. How can I stay free and relaxed? I took a very simple idea from traveling. When on the road, the simple thing to do is count your bags so you don’t leave them behind. Don’t worry about how big or what color, just count them. In flute practice, I will try to do this with my stress points, just count them. At the moment I have 3, so when I re-take the flute after a break or a breath, or when I stop a passage, I do a count. It is so much simpler than thinking: right shoulder-blade out, left shoulder down, lower back open. Just 1-2-3 and I am aligned again. So stress gets left behind, not good practice habits 🙂

Just for the my records and for those who give a rat’s, here are the pieces I will be performing between the 22nd of August and the 18th of November. (Not including December because I am not sure yet, but there will be concerts!)

Solo:

Rebecca Saunders – Bite for bass flute (premiere)

Farzia Fallah – Poshte Hichestan (premiere for C flute)Ensemble:

Gordon Kampe – Arien/Zitronen

Tom Johnson – Self Portrait

G. Ligeti – Aventures/Nouvelles Aventures

Frank Zappa – Black Page and other works

Edgar Varese – Ionisation (Castanets and Guiro)

Luciano Berio – Points on a Curve to Find

Steve Reich – Radio Rewrite

Harry Partch – Delusion of the Fury

Hanspeter Kyburz – Danse Aveugle

Toshio Hosokawa – Slow Dance

Michael Finnessy – MuFa

John Cage – 16 Dances

Liza Lim – Tree of Codes (opera)

Claudia Molitor – Walking with Partch

Harry Partch – Li Po “Intruder’ (maybe!)

Michael Wertmüller – antagonisme controle

G. Kurtag – Bagatellen

Enno Poppe – Stoff -

Intonation Exercises

Here is a compendium of intonation exercises I have written over the years. They require either two players or one player and a sound-generator such as a tuner or an app. (The exception is the “Exchange” exercise.)

These exercises are based on being able to discern and manipulate difference tones, and contain a basic introduction to just intonation.

If you distribute these exercises please give credit where it is due. Have fun!