Here is a running list of salient points from my separate blog entries together in one place. This is a work in progress, so any tips are welcome. For more advice on composing for flute, you can view all entries in the categories: Composing for Flute, or pet peeves.

Range of the Flute and the Characteristics of its Octaves: for a full rant on the subject, read here.

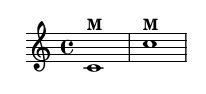

The first octave of the flute has a special timbre due to the fundamental being relatively

The first octave of the flute has a special timbre due to the fundamental being relatively

weak in relation to its first partial ( a partial can also be called a harmonic partial or overtone). Projection over other sounds doesn’t come easily in this register. Dynamics are possible and are produced by adding and subtracting the upper partials of the sound.

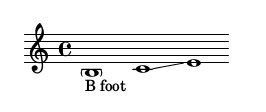

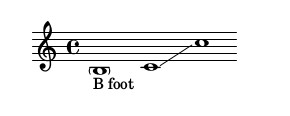

A special word about the lowest notes of the flute. These are produced by the right hand pinky on the foot joint of the flute. Fast passages that are not purely chromatic or scalar can be difficult because they require sideways motion. Consider writing fast passages for these lowest notes on alto flute. A fluid motion from B – C# is not possible because the C/natural roller lies in between the B roller and the C# lever.

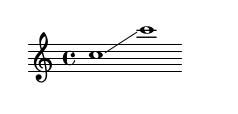

The middle C# of the flute deserves special mention. Because it is the open note of the flute it has a naturally hollow timbre. Debussy used this to great effect in the opening of his L’Après-midi d’un Faune. Although it technically lies in the second octave, its projection possibilities are limited due to its lack of upper partials in the sound.

The middle C# of the flute deserves special mention. Because it is the open note of the flute it has a naturally hollow timbre. Debussy used this to great effect in the opening of his L’Après-midi d’un Faune. Although it technically lies in the second octave, its projection possibilities are limited due to its lack of upper partials in the sound.

The second octave of the flute doesn’t contain as many caveats, but beware writing these notes as harmonics (see below).

The second octave of the flute doesn’t contain as many caveats, but beware writing these notes as harmonics (see below).

The third octave is where the flute can really shine in an orchestral situation. However, sustained quiet passages, or dynamics al niente or dal niente can be difficult for the highest notes of this range. It may better to use piccolo, especially if the passage contains rapid notes. At the highest latitudes, writing fast passages on piccolo instead of flute can save a flutist hours of practice and physical therapy.

One assumption composers commonly make is to write loud sustained passages in this range on piccolo instead of the flute, thinking that the piccolo will project more. The third octave of the flute projects quite differently than the second octave of the piccolo. If you want a brilliant sound for sustained notes this register, use flute and not piccolo. It is really a color choice.

A mistake composers often make is to write these notes as harmonics, thinking that this will make them quieter and give them a more détimbré sound. That may be so on string instruments, but from around F or G up in this register on the flute, harmonics require more air and a higher air speed, and are therefore difficult to produce quietly. If you want a special quiet sound, find a special fingering that vents the sound and doesn’t rely on an overblown fundamental. However, if you want a full overblown sound, the harmonics in this register work very well.

Use the fourth octave sparingly, especially when writing for young players. A non-harmful 4th octave technique takes time to develop. In ensemble or orchestral music with extended or technical passages in this register, please consider using piccolo. If the passage contains sustained notes in this register, piccolo is also better.

In this range, the flute will be heard, no matter how many ppp‘s a composer writes. Loud dynamics only. The remarks about harmonics in the third octave also apply here.

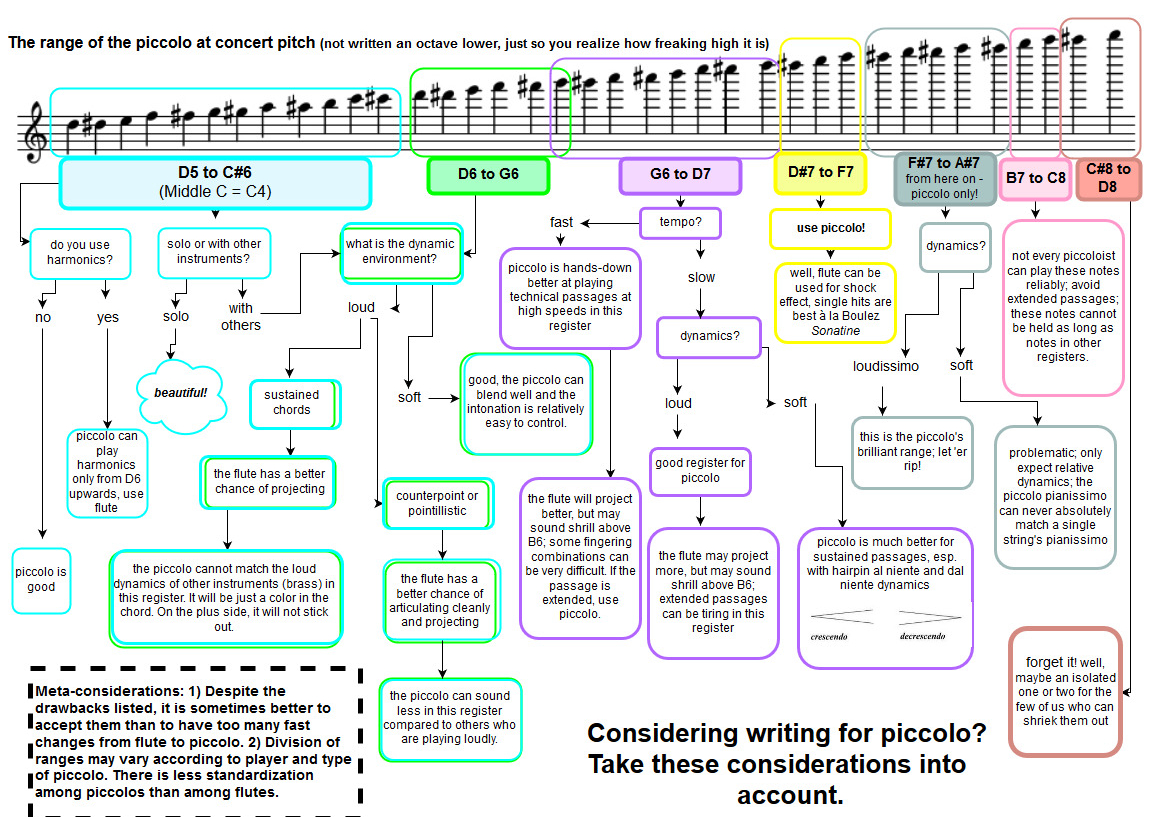

If you have read this far and this high, and are wondering whether to use flute or piccolo, here is a flow chart to help you decide (or give you too many options):

Trills: avoid the following trills on the flute. They involve a sideways motion of the right hand little finger instead of the quick up-down motion that produces a good trill.

Harmonics:

Since harmonics are produced by overblowing on the flute, the first octave notes cannot be produced as harmonics. The E-natural, F and F-sharp in the second octave are not available as harmonics because the fingering is the same in the first octave as in the second. They are already harmonics.

As mentioned above, quiet harmonics are difficult above the upper third register. If you want quiet, especially sustained sounds with a special timbre, consider using alternate fingerings rather than true harmonics. Read why here.

Multiphonics: Basic guidelines:

- write the fingering (or for extended passages where this will clutter the notation, provide the fingering in the performance instructions).

- use an intuitive template for writing the fingerings, such as those in Robert Dick’s The Other Flute. A good online fingering template can be found here.

- unless you are a flutist yourself, I would not advise using online resources such as The Virtual Flutist. When a resource shows every single pitch that can be produced by a certain fingering, it doesn’t necessarily follow that a multiphonic can be created from these pitches. Try it with a live player before trusting a theoretical projection of the flute’s acoustic response.

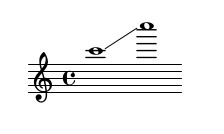

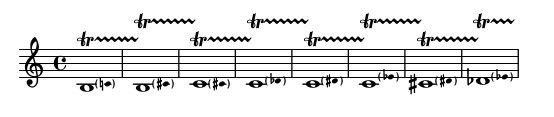

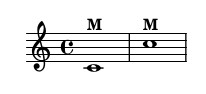

- if you want to give the flutist a choice of multiphonics based around a certain pitch,

beware that the lowest pitches will produce only harmonic multiphonics. The second measure, the C in the second octave, gives more inharmonic possibilities than the first.

beware that the lowest pitches will produce only harmonic multiphonics. The second measure, the C in the second octave, gives more inharmonic possibilities than the first. - take care of the surrounding dynamics in an ensemble situation. The flutist has to be able to hear him/herself well enough to produce these sounds accurately.

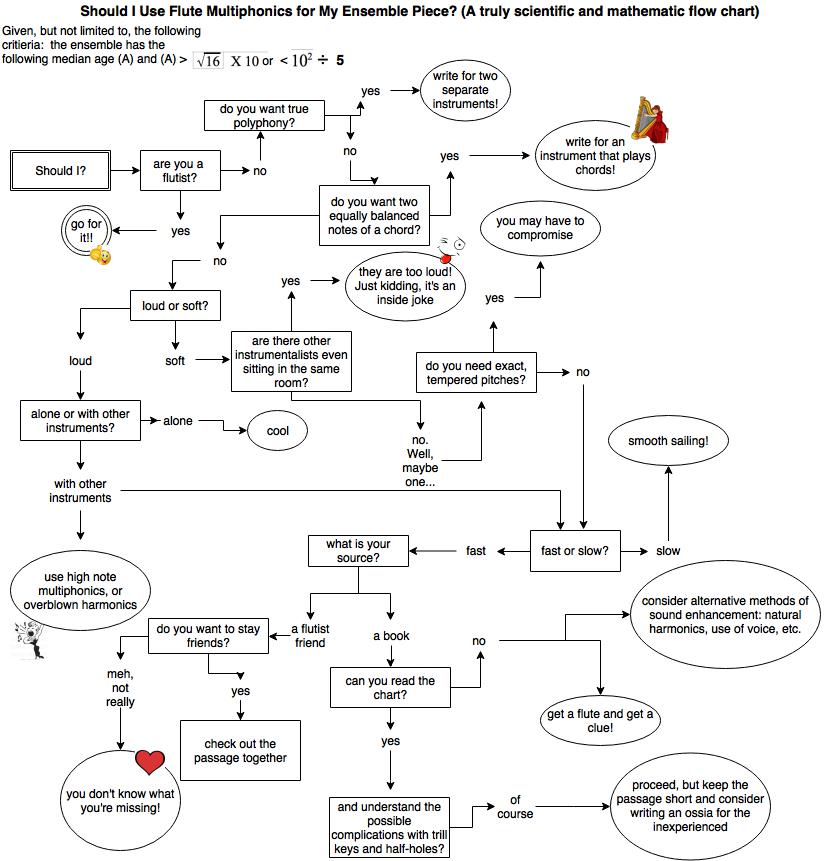

For Q & A about writing for mulitphonics, read here. Or here is a handy flow chart as to clear up some of your questions. Please note this is regarding ensemble writing, not necessarily solo writing:

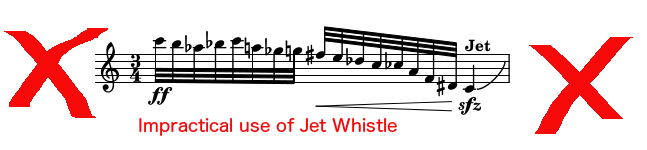

Jet Whistle: A really high-powered jet whistle needs time and quite a bit of air to set up. For best effect, have a rest (ca. one second) before and after a jet whistle. It is too often that composers think of a jet whistle as a kind of climax or punctuation after a phrase, as in the following example. But there are two problems: 1) There is no time to set the embouchure 2) There is no time to breathe. It bears repeating, if you want a full force jet whistle, give the player time to set it up.

Harmful things:

- Slamming hands onto the key work. A key click is OK.

- Immersing part of the flute in water.

- Closed embouchure techniques on wooden mouthpieces. (Tongue ram, jet whistle, etc.) Saliva contains enzymes that will degrade the wood over time.

- Extreme temperatures.

Some pet peeves:

- Using empty note heads to indicate air or aeolian sounds in an ensemble situation. Please see my tips on this subject.

- Extended techniques stacked up on top of one another. It is easy to think that this will make the sound more interesting and intense. Some techniques cancel each other out and just muddy the waters. Better to pick a few that work acoustically well together.

- Landscape layout for parts. The pages take up too much horizontal space on the music stand – having more than 2 pages open requires more stands. If you need to enlarge the score, it takes up even more room. See how Grisey’s Périodes looks on the music stand – impractical: